Running CFD simulations on a single core allows us to perform simple 2D simulations, perhaps even with turbulence models activated, to extract some simple results. However, once we want to run some more realistic cases of industrial or academic relevance, we often have to utilise parallelisation to receive simulation results in a fraction of the time compared to a single-core simulation.

If parallelisation were a simple affair, i.e. simply telling our CFD solver how many cores to use and then expecting a proportional speed-up, we wouldn’t need this article, and CFD engineers would not be forced to work with eccentric computer scientists to get good parallelisation performance.

Parallelisation is a simple topic at first glance, but the devil is in the details. We will learn about how parallel performance is achieved on high-performance computing (HPC) clusters, which hardware is used, how to achieve good parallel performance (and how to quantify it), as well as the cost of parallelisation. We will also look at concrete code examples for parallelising a simple CFD solver using common parallelisation approaches for running simulations in parallel on the CPU and GPU.

If you have the feeling that parallelisation is a topic you haven’t spent much time with but ought to give it some attention, then this article is for you. It shows you how to extract the most computational power out of your simulations, how to use computational resources responsibly, as well as what bottlenecks exist in parallel computing that still require ongoing research.

It is one of those articles that likely takes a bit longer to read through, so I hope you have a strong brew next to you. This article was produced using approximately 31 TWINGINGS Earl Grey teas, 13 Meßmer Madame Grey teas, 17 17-grain Walnut-Almond teas, and about 5 KitKat hot chocolates. I recommend you consume the same. Here is to violent bladder failure.

Download Resources

All developed code and resources in this article are available for download. If you are encountering issues running any of the scripts, please refer to the instructions for running scripts downloaded from this website.

- Download: Parallelised Heat equation

In this series

- Part 1: How to Derive the Navier-Stokes Equations: From start to end

- Part 2: What are Hyperbolic, parabolic, and elliptic equations in CFD?

- Part 3: How to discretise the Navier-Stokes equations

- Part 4: Explicit vs. Implicit time integration and the CFL condition

- Part 5: Space and time integration schemes for CFD applications

- Part 6: How to implement boundary conditions in CFD

- Part 7: How to solve incompressible and compressible flows in CFD

- Part 8: The origin of turbulence and Direct Numerical Simulations (DNS)

- Part 9: The introduction to Large Eddy Simulations (LES) I wish I had

- Part 10: All you need to know about RANS turbulence modelling in one article

- Part 11: Advanced RANS and hybrid RANS/LES turbulence modelling in CFD

- Part 12: Mesh generation in CFD: All you need to know in one article

- Part 13: CFD on Steroids: High-performance computing and code parallelisation

In this article

- Introduction

- Flynn's taxonomy: The 4 types of parallelisation

- Understanding the hardware our simulations run on

- Performance and bottlenecks

- Parallelisation frameworks

- Challenges in code parallelisation for CFD applications

- Summary

Introduction

We all remember our humble beginnings in CFD. For me, it was the classical NACA 0012 simulation at a zero-degree angle of attack. While I rarely jump out of my seat these days when I see the contour plots around this airfoil, back then, I was blown away. It was so powerful that I decided that CFD is my calling, my passion, my future. I even went as far as changing my Facebook profile picture to this contour plot (is Facebook still alive?).

Chances are, your first simulation wasn’t much different, at least in terms of complexity. You likely ran a tutorial case that could be executed on your PC or laptop in a reasonable amount of time. Perhaps you made some changes to the input, played around with the test cases and, like me, realised that changes to the input had drastic effects on the simulation.

In my case, changing the angle of attack so that the airfoil would stall meant that convergence was no longer given. I found that fascinating and wanted to know more; others would have, understandably, given up, but then again, those would likely not commit to reading an unnecessarily long article on parallelisation and high-performance computing in CFD with the odd unhinged commentary.

Eventually, you and I gained confidence in our CFD skills, and we wanted to simulate our own cases, likely something more exciting than a 2D channel flow. So, we created 3D geometries and then realised that our PCs or laptops would not be able to run those simulations in a few minutes. I remember having my laptop and PC at that time running in parallel, both doing one simulation each and both running for about 24 hours per simulation. That was my first serious attempt at CFD; yours may have been similar.

But then, I was introduced to the world of high-performance computing (HPC). HPC to an aspiring CFD practitioner is like the discovery of Viagra for a retired Person; it’s a game changer (or starter?). All of a sudden, I was able to run simulations in less than an hour that would otherwise take me days. This was reason enough to get acquainted with HPC, even though there was a step learning curve (I also had an HPC assignment due, which likely contributed to my motivation).

When we are dealing with HPC, we typically mean HPC clusters, which sometimes are also called supercomputers, because whoever came up with this name was suffering a lack of serious creativity. Here are my takes:

- The Mother of all FLOPs (MOAF)

- Clusterfuck

- Cache Me If You Can

An HPC cluster is nothing but a bunch of PCs chained together. The simplest cluster we can think of is a bunch of Raspberry Pies linked together. There is even an official tutorial by the makers of Raspberry Pi, showing you how you can do that. It is weirdly affordable, and you can decide next time you buy a new gaming PC if you really need that or your own HPC cluster on your desk.

While the Raspberry Pi example is good to understand how a cluster works, if we need serious computing power, as we do for CFD applications, we really want to use dedicated hardware. All major chip manufacturers offer dedicated compute hardware to build clusters, and these are somewhat different to what you would find in PCs and laptops. The main difference is speed and performance. They have more cores, more memory, and a network connection so fast that it would melt your router (maybe).

Twice a year, TOP500 uploads a list of the 500 fastest clusterfucks HPC clusters in the world. They list, among other details, the number of cores, the performance, as well as the power required to keep the cluster running. The performance is measured in how many floating-point operations can be done per second on the cluster. The unit is PFLOPs, or Peta Floating-point Operations Per second, where Peta stands for 10^{15}.

If we designed a new cluster, and we could get a staggering 1 PFLOPs in performance, we could perform 10^{15} multiplications/divisions/additions/subtractions per second on floating point numbers. Let’s put this into perspective. If we have a mesh with 10 billion cells, we have 10^{10} cells. We can perform 10^{15} / 10^{10} = 10^5, or 100,000 operations per second on each cell. Imagine what you could simulate with 10 billion cells. Direct Numerical Simulations (DNS) would be the norm.

Where would this impressive cluster rank in the TOP500? Nowhere. 1 PFLOPs in performance isn’t impressive any more, and we likely wouldn’t even make the top 1000. These days, we have achieved exascale computing. That is, instead of measuring performance in PFLOPs, we use EFLOPs, or Exa FLOPs. Exa stands for 10^{18}, and the best supercomputers in the world go beyond 1 EFLOPs.

All of this performance needs to be leveraged, and this is where code parallelisation comes in. We can’t just write a CFD solver and then hope that our HPC cluster will be able to run it. If we write software without consideration given to parallelisation, we can’t use more than one core. There is no point running our software on a 10-million-core cluster if we can only use one of them.

Thus, we need to parallelise our code, meaning we have to modify our code so it can use more than 1 core. With that come unique challenges, and I want to explore those in this article, as well as performance metrics that help us to measure if we have achieved a good parallel performance, and some frameworks we can use to parallelise our code.

We have our work cut out for ourselves; let us see how we can do that.

Flynn’s taxonomy: The 4 types of parallelisation

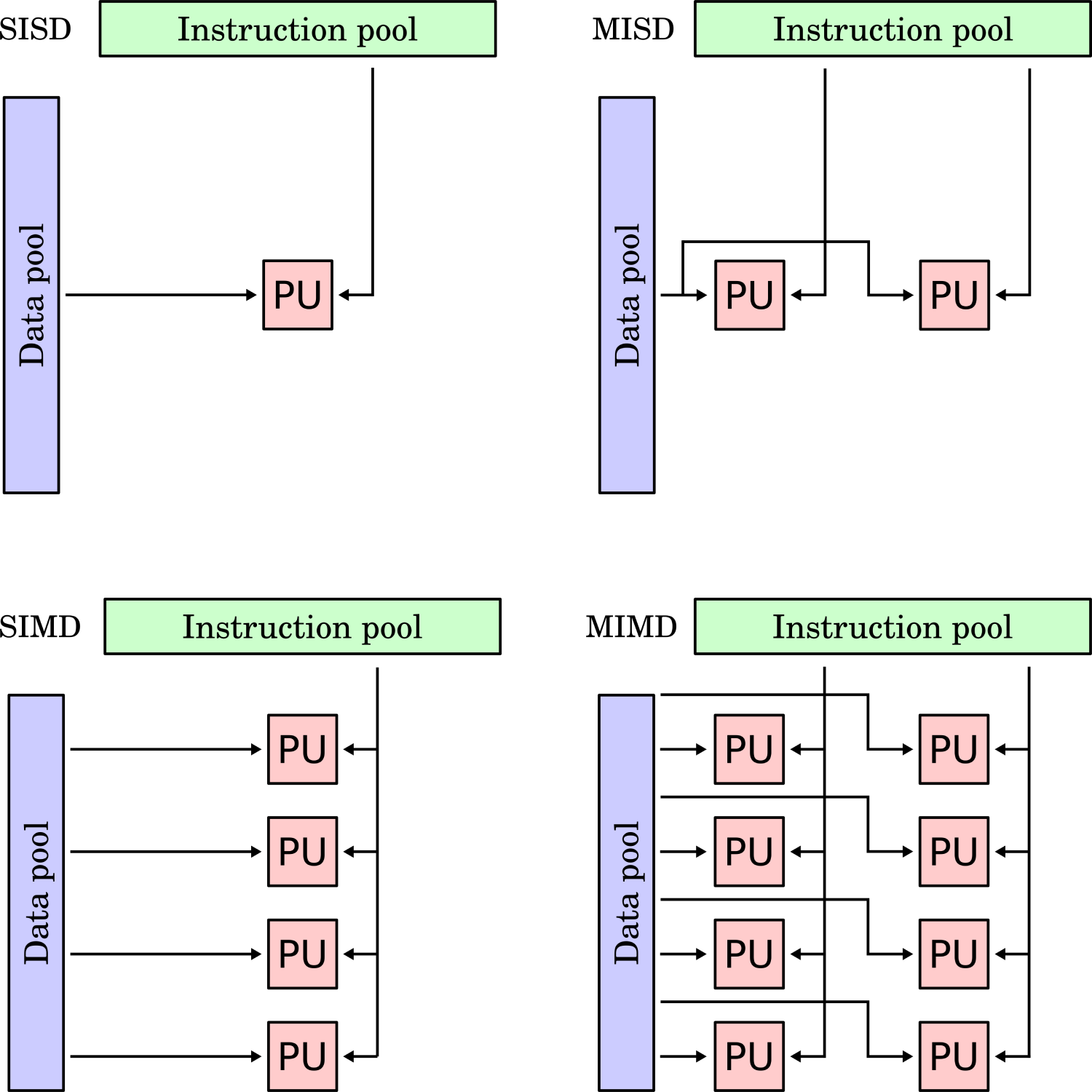

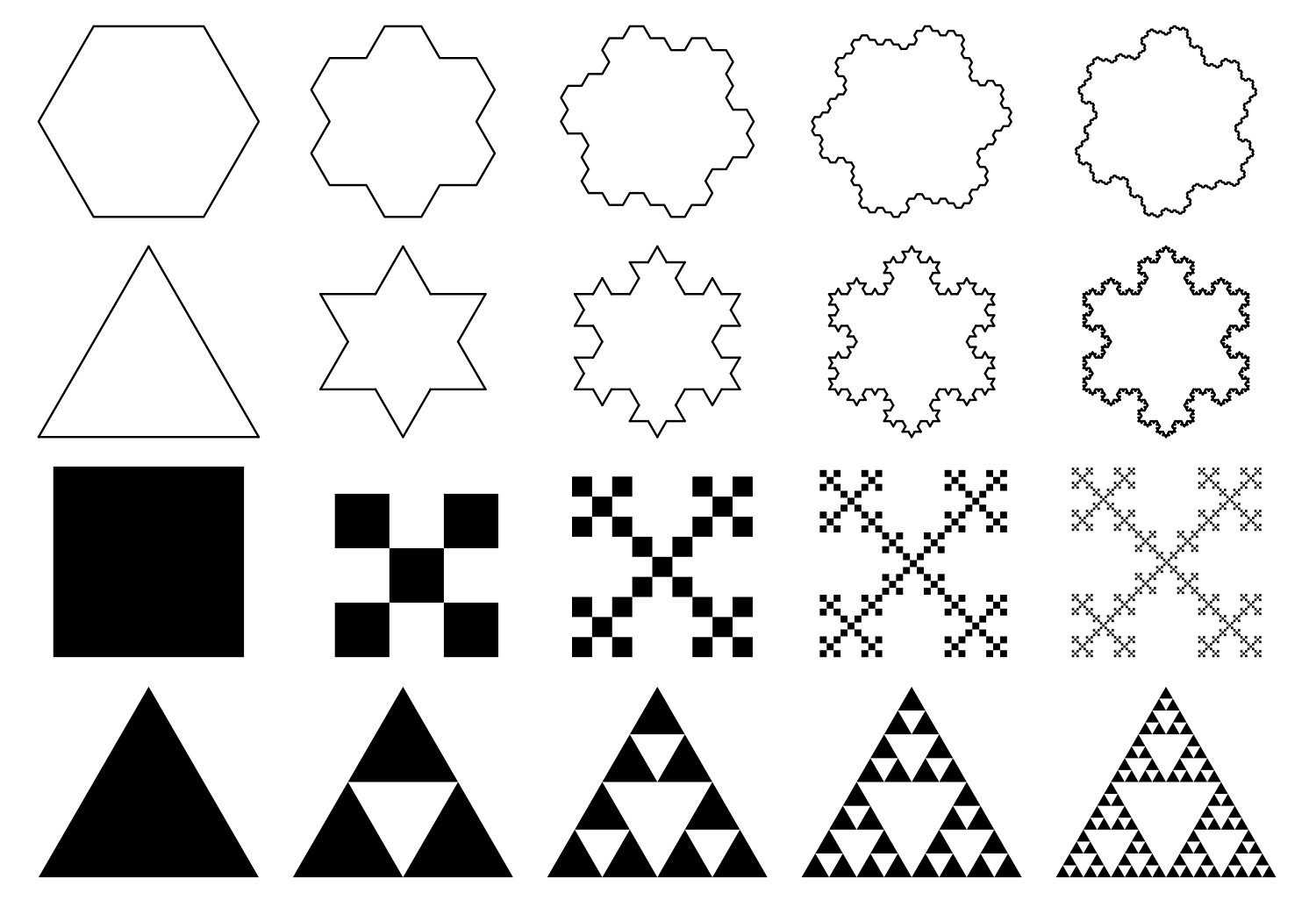

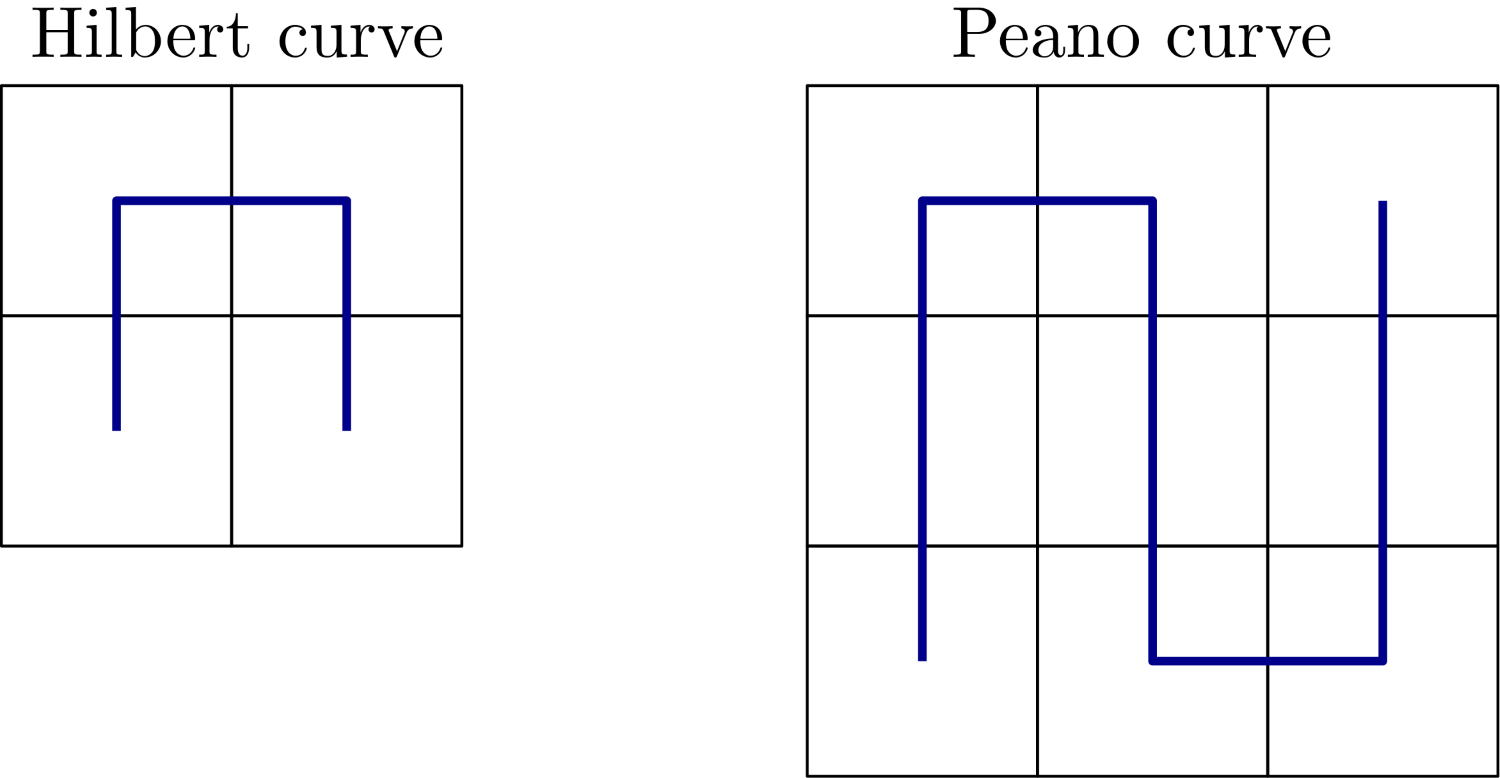

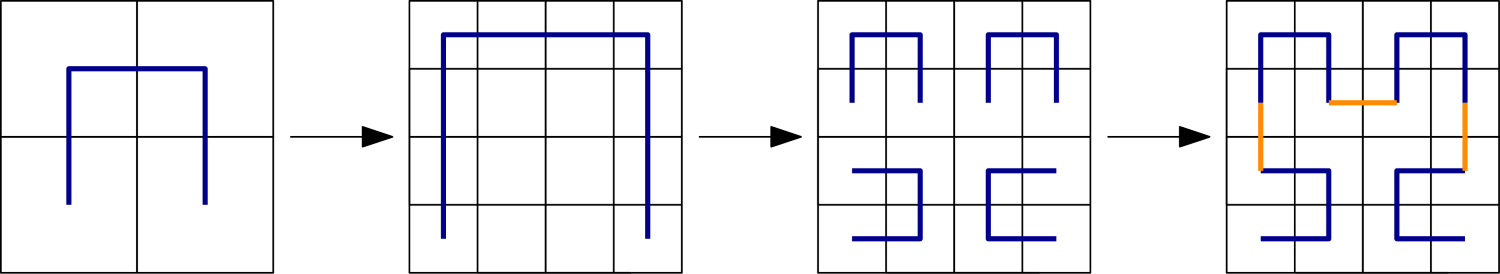

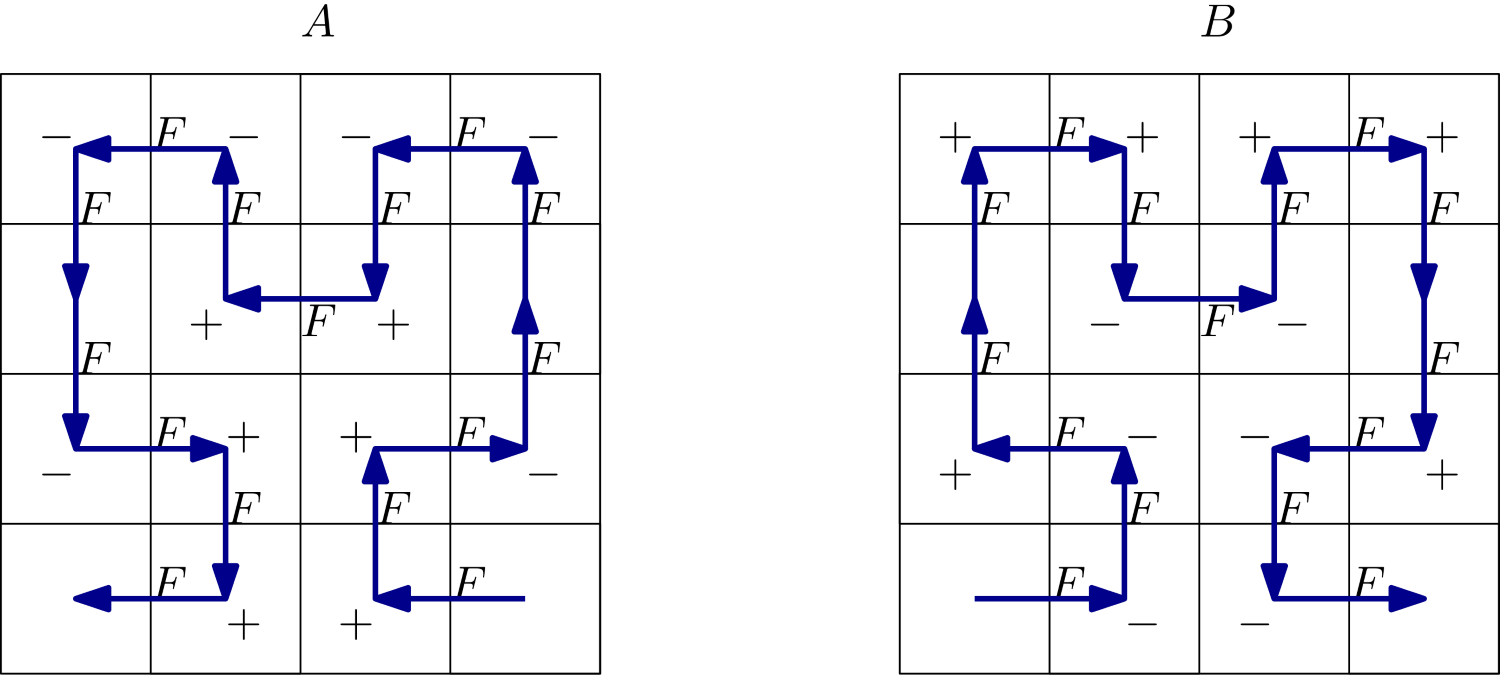

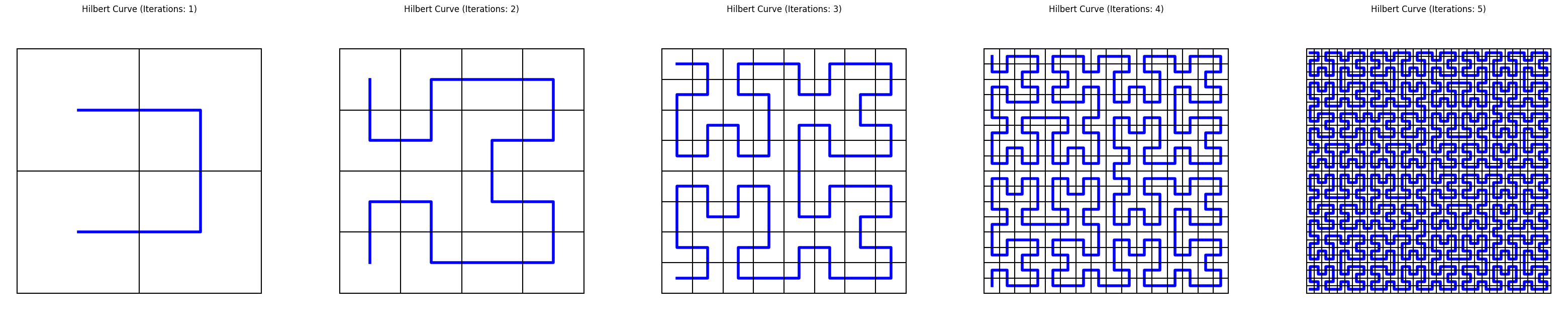

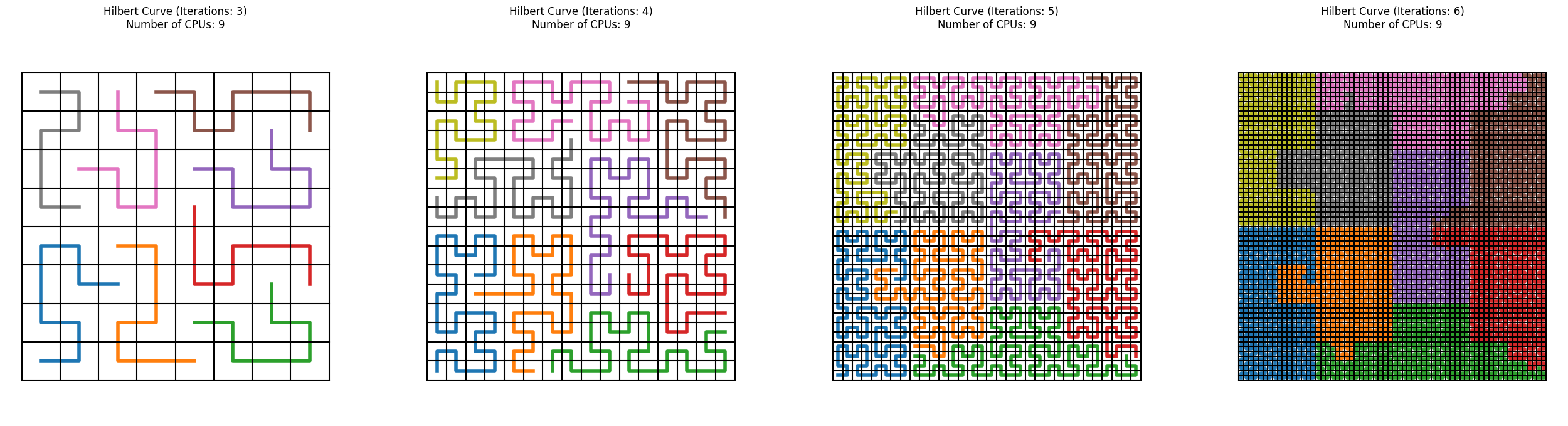

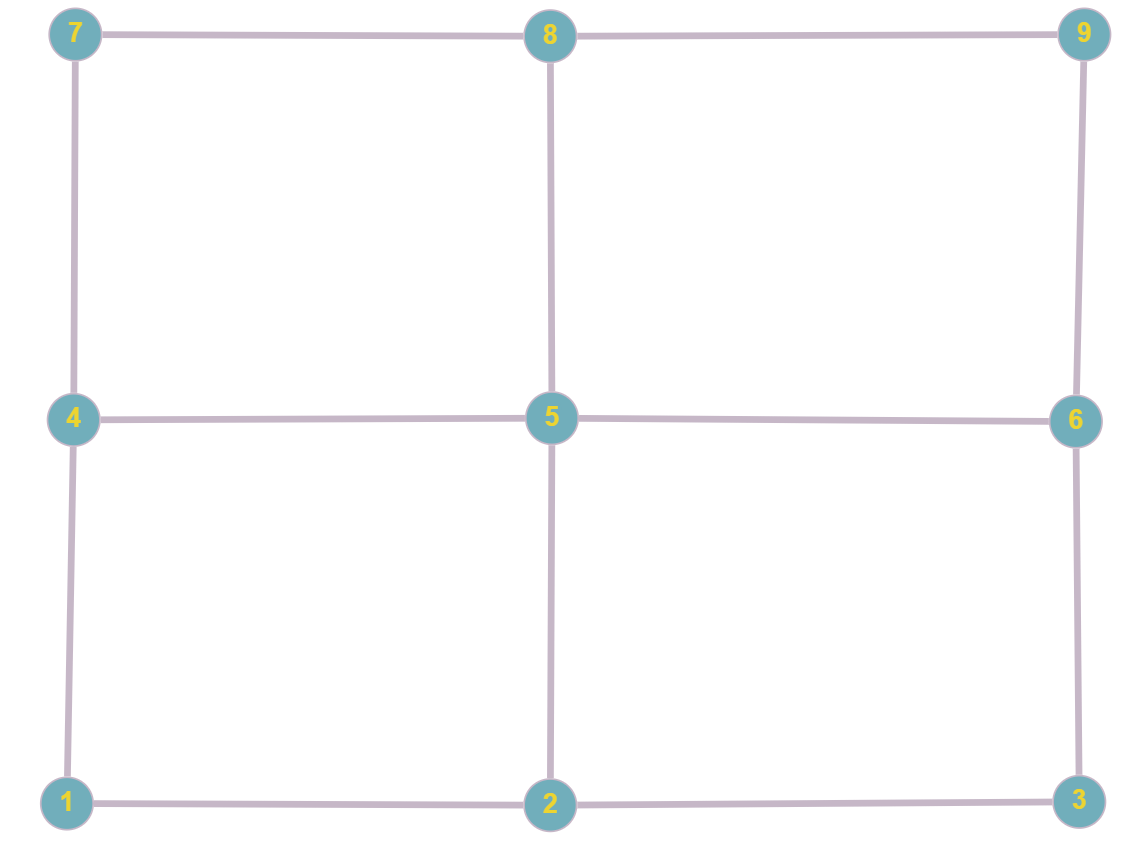

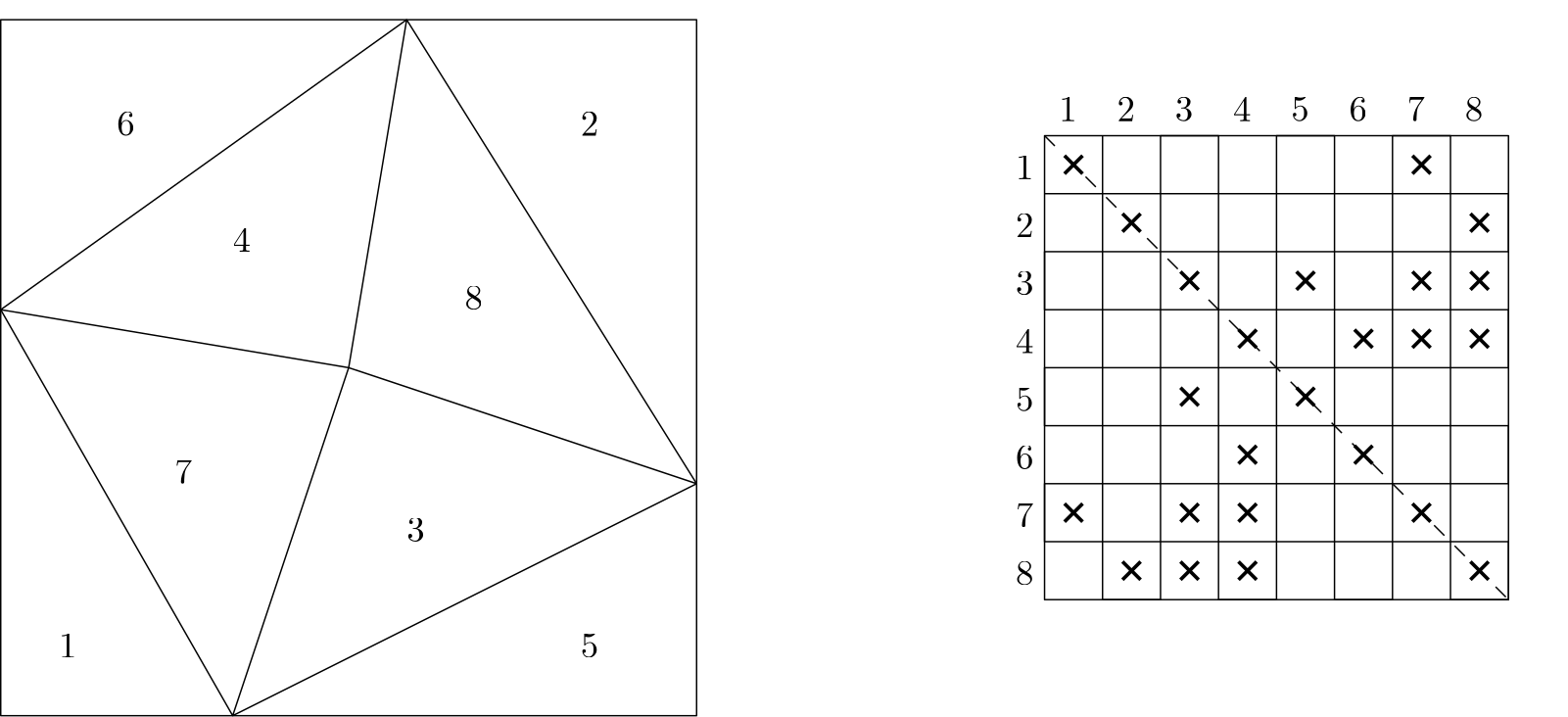

Flynn’s taxonomy allows us to identify 4 separate parallelisation approaches based on instruction and data parallelism. If we are dealing with multiple instructions, each processor will work on separate instructions. If we have multiple data sets, this means that processors work on different data. An overview of Flynn’s taxonomy is given in the following figure:

When I first saw this classification, I had difficulties understanding it; it seemed a bit abstract. So let’s breathe some life into this figure and give examples for each quadrant.

Single instruction, single data (SISD)

Single instruction, single data (SISD) is the paradigm you will be most familiar with. It means we have a single instruction, executed by a single processor, and it is working on a piece of data. If you have ever written a simple CFD solver, even just a code to solve a model equation like the heat diffusion, advection, or Burgers equation, you wrote a SISD program.

You had a single core working through your instructions, e.g. first compute the gradients, then perform the time integration, then update the solution, etc. All of this was performed by a single processor, and all of this was done one at a time. In terms of data, that was coming from RAM, and all of that RAM was available to you. Thus, your processor used only one set of instructions, and it was operating in a single set of memory. This is also called a sequential application.

Single instruction, multiple data (SIMD)

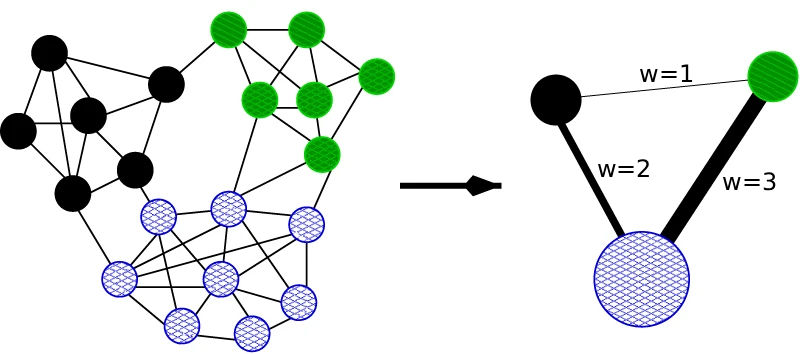

Single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) is the most important parallelisation category for us in CFD. When we talk about code parallelisation, we talk about SIMD parallelisation. Code parallelisation means that we now use more than one processor to run our code. All processors execute the same instruction, but they operate on different data.

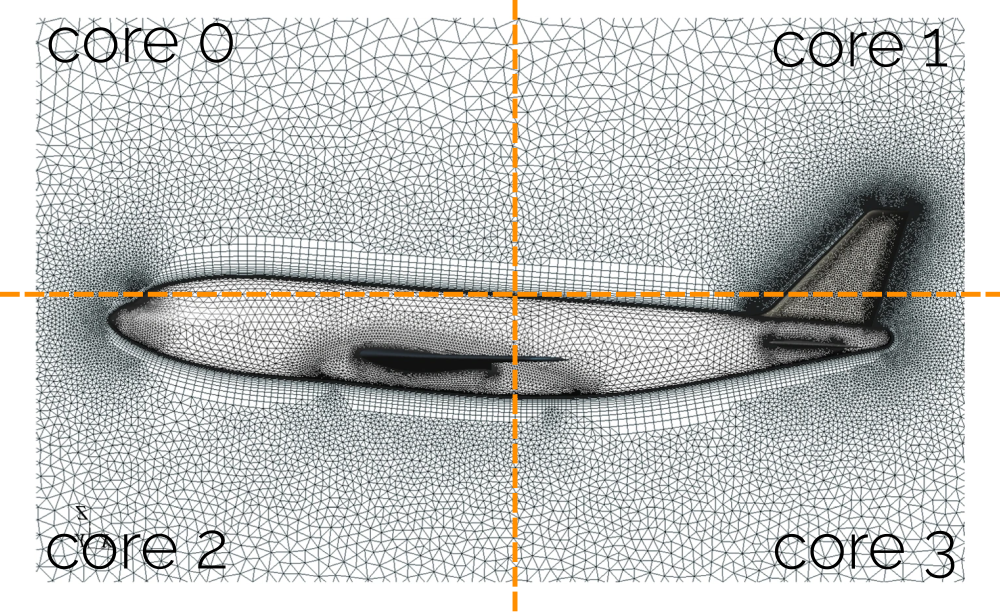

In practice, this means that each processor will still perform the same steps as in our previous example, i.e. each processor will compute gradients, then integrate in time, etc. They will all work at the same time but on different data. This means that if I want to parallelise my code and I run a simulation with a 10 million cell mesh on 4 processors, each processor will perform the gradient calculation, time integration, etc., on only 2.5 million cells.

The speed-up, then, is coming from the fact that for each individual processor, it seems like the problem size is only 2.5 million cells, rather than the full 10 million cells, and so in an ideal world, we would expect (or rather, hope) that we can a 4-times faster simulation with 4 processors compared to a single processor simulation (e.g. SISD).

Multiple instruction, single data (MISD)

Multiple instruction, single data (MISD) is a concept that only really exists for completeness in Flynn’s taxonomy. While this parallelisation does exist in the real world, it does not make sense in the world of high-performance computing. The reason is that MISD performs multiple different instructions, but all on the same data. If we take the example from before, each processor gets the full 10 million cells mesh. If they all have to operate on it, we won’t see a speed-up.

So why would we ever use this? In systems where redundancies are important, MISD is the way to go. For example, an aeroplane measures airspeed with 3 different sensors. It does that because knowing the airspeed is the difference between flying and stalling (and thus falling out of the sky). Thus, the onboard computers that calculate the airspeed are getting their input from three separate sensors (which all provide the same data), and because we have more than one computer, we have multiple instructions operating on this single dataset.

So, MISD is an important paradigm, but just not in high-performance computing.

Multiple instruction, multiple data (MIMD)

If you like complexity, then Multiple Instruction, multiple data (MIMD) is for you. It contains the same multiple data concept we already saw in SIMD, and this really is where computational gains are coming in (breaking a larger problem down into smaller subdomains and solving these smaller subdomains for faster simulation times).

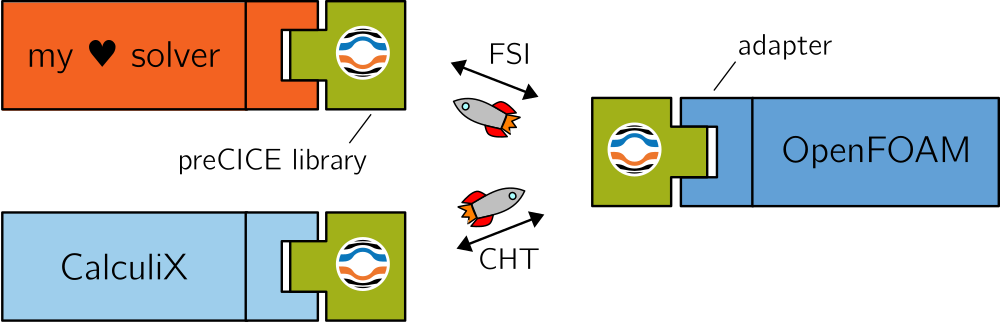

With MIMD, we open ourselves up to multiphysics problems. The simplest and most studied one would be Fluid-Structure Interactions (FSI). Here, we solve a CFD problem and couple that with an FEA solver. Both the CFD and FEA solver have their own data to work on (multiple data). A CFD solver also would have different instructions compared to a FEA solver (multiple instructions), e.g. there is no “solve continuity equation” in the FEA solver, nor is there a “compute displacements and von Mises stresses” in the CFD solver.

Whenever we are coupling two or more solvers together, we get into multiple instructions territory. As long as we leverage multiple data as well, we have a viable parallelisation strategy. The challenges arise here in determining which resources to allocate to which solvers. If we want to perform a single time integration between CFD and FEA, then the FEA solver may only take 1/5 of the time to update the timestep compared to the CFD solver. If we give them the same resources, the FEA solver will waste most of them.

Thus, we need to think about how to balance resources allocated to each solver, and this is known as load balancing. This is a crucial aspect in high-performance computing, and if we don’t have a good load balance in our simulation, all of our code parallelisation is pointless.

For completeness, load balancing also affects SIMD, i.e. if we have 10 million cells and 4 processors, we want to make sure that each processor gets an equal amount of work (i.e. 2.5 million cells). If we give 3 processors just 1 million cells and the remaining processor 7 million cells, then we are going to have a load imbalance. On paper, this may seem like a simple problem, but in reality, it isn’t, and we will talk a lot more about the challenges later when we deal with domain decomposition techniques.

Understanding the hardware our simulations run on

Understanding computer hardware is really important if you want to understand how performance is achieved (or lost). You may think, for example, that once your code is parallelised, you get an automatic speed-up if you use more processors. This is certainly the approach I see new students make. Whenever I ask them why they are using 96 processors for their simulation, the answer is usually “because that is the maximum I am allowed to use“. That is the wrong answer.

If you have access to a CFD solver, set up a simple test case, something with 10000 cells or less and then run this on 1 processor and the max number of processors available to you. Say you have a 4-core CPU, then run this with 4 processors. What you will see is that your 4-processor simulation is slower than your 1-processor simulation.

The opposite can also happen. Say you set up a simulation to run on a single core. You then parallelise your code and run the simulation on 4 processors. You would expect the simulation to speed up by, at most, a factor of 4. You measure the speed up, and you see that your actual speed up is 5. All of this can be explained by understanding the computer hardware.

Some time ago, my beloved custom-built CFD workstation PC died (I say custom-built CFD workstation, this is the excuse we give ourselves to splurge on a high-spec PC to run some CFD simulations, only to realise that your CFD workstation is also an excellent gaming rig. The amount of yoghurt and excavators I have delivered to Scotland in European Truck Simulator 2 is embarrassingly high … just me?).

I must have told that story before, but in a nutshell, driving at night gives probably the best immersion, but trucks also have quite a few gears, and so I was busy shifting gears while traversing the Scottish Highlands. It turns out that if your partner tries to sleep in the same room, those gear shifts are really annoying, and she told me as much. Suffice it to say, I no longer have access rights to my steering wheel.

In any case, that PC died, and so I bought another somewhat decent PC, at least spec-wise. It had a GIGABYTE motherboard, a brand I had no idea existed before, but it seemed legit, so I didn’t question it. The PC arrived, worked a good 2 months, so the PC could no longer be returned, and at that point, the PC started to crash hard. 10 bluescreens of death or more were common per day, and they would happen out of the blue (no pun intended).

After trying to reinstall Windows about 10 times, changing hardware, and examining crash dumps, I was ready to give up on my PC. And then, I saw this video:

Apparently, the motherboard I had came with malware on the hardware level. No matter what changes I made to my operating system, the motherboard would randomly crash my PC, and that’s also why all of the crash dumps would not make any sense whatsoever. I upgraded the BIOS, but even that wasn’t working. So, the issue may have been somewhere else entirely, but I could not be bothered investigating this further.

I told my line manager that my PC died and I needed a new CFD workstation. I got another beefy machine, and while I use it for work (I am writing this article currently on it), it is also exceptionally well-suited to play Rocket League on it. Who would have thought?

There is a point to make here (believe it or not). I thought I could tell you about this PC story and then transition to the PC hardware. I wanted to take a picture of that PC (for some reason, I still hold on to it) and show you the motherboard, RAM, CPU, GPU, hard disk, etc. and then go through each component and say something like “this is the most expensive picture I ever took”, as in, I can’t use it anymore as a PC, so it is essentially an expensive photo model. But then I took the picture, and this is what I got:

Wow, I can show you where the fan is sitting, and that’s probably it. Why is there so much empty space (and dust)? It is not just a bad PC, it’s also a pretty bad photo model. Turns out I should have just googled a motherboard picture and saved you from my random sidebar, but you are still here, so you get partial blame, too.

So, let’s look at a normal motherboard:

Most will likely be familiar with this. We have our central processing unit (CPU) in the middle, slightly to the right (hidden under the metallic cover). Below that are 4 slots to insert random access memory (RAM) modules, and to the left are 2 Peripheral Component Interconnect (PCI) slots for graphical processing units (GPUs). Well, there are other things we could put here, but typically, we only place GPUs here.

I like this motherboard because on the top right, it states: “TUF GAMING Z590 MILITARY GRADE PERFORMANCE”. What exactly is military-grade performance? I know that products sometimes boast military-grade durability when they follow, for example, the military standard for stress testing. But what is military-grade performance? As one source succinctly puts it: Military-grade is just military-grade marketing bullshit. Moving on.

We can summarise that a normal PC, or laptop, will have a CPU, some RAM, some main memory (hard disk), as well as potentially some add-on devices like a GPU. Add some cooling for CPUs and GPUs to avoid overheating, and you have yourself a PC. Probably, I am not telling you anything new here. But let’s now explore what a high-performance computing cluster looks like.

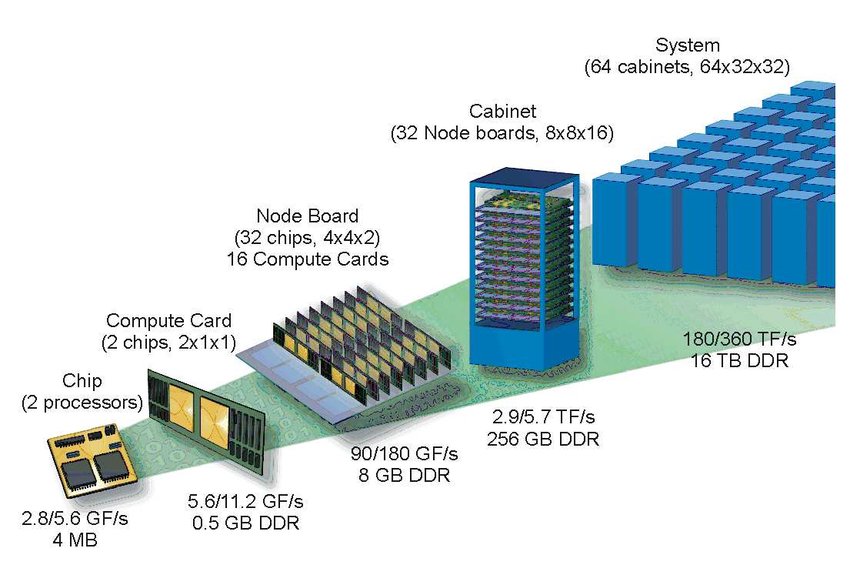

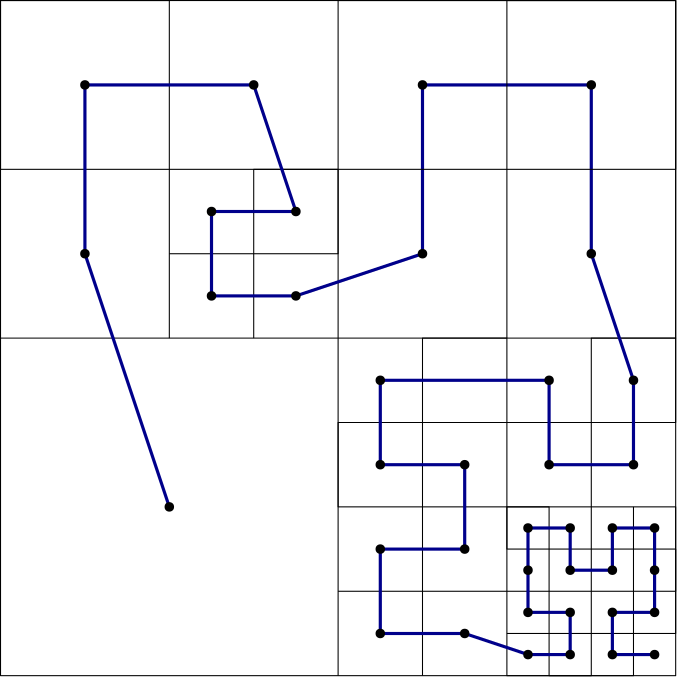

The following schematic shows how an HPC cluster is structured.

Starting on the right, we have the entire HPC cluster. Its size is usually large enough to warrant building an entire building around it, which is sometimes misleadingly called a data centre (though data centres can also be interpreted as a catch-all name for anything from long-term storage (e.g. Dropbox), to cloud computing, to high-performance computing clusters).

The HPC cluster, or system, is made up of individual cabinets. Each of these cabinets will house a number of racks (which are called node boards in the schematic above), which contain a number of compute nodes (called compute cards in the schematic above). If you are talking to a professional, they may just use the word node, and it appears that the infantile urge to abbreviate everything (LOL, ROFL, LMAO, yes, I know, I’m old) does not stop when you have a PhD (which is an abbreviation as well, now that I think about it …).

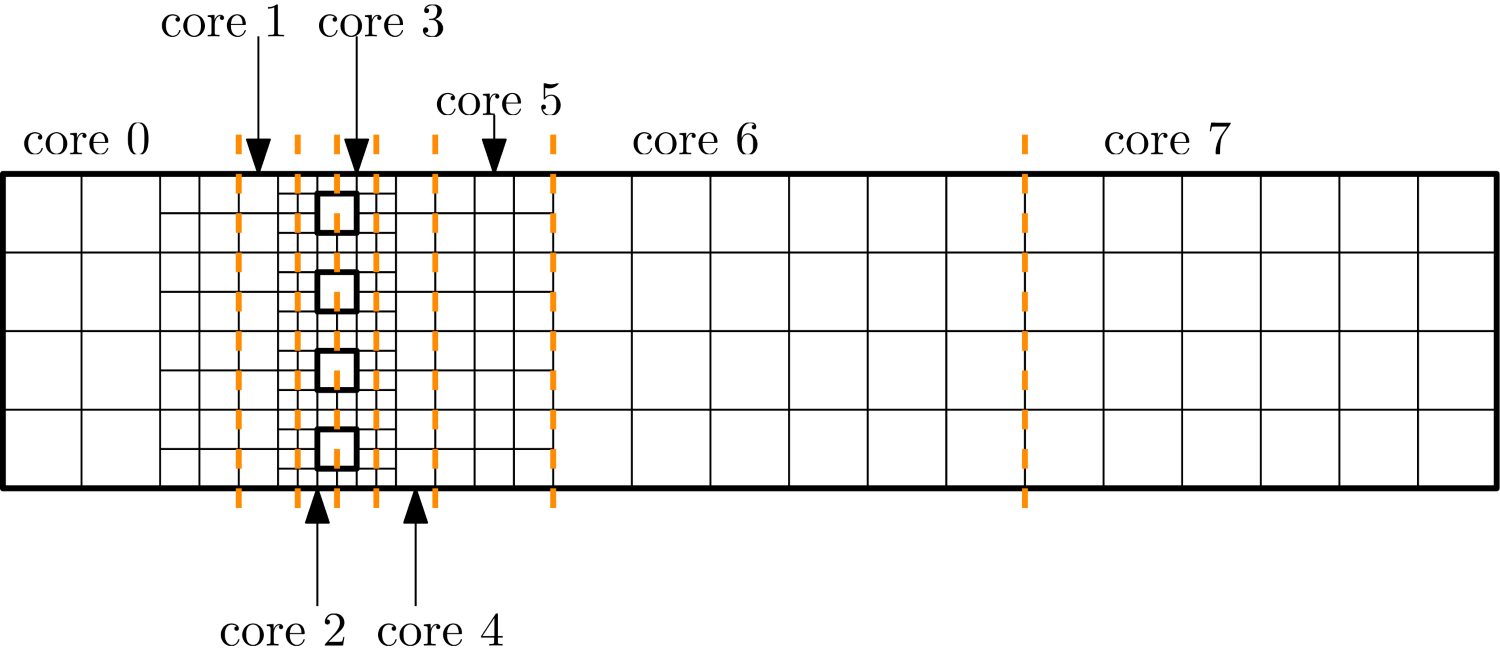

Each node (oh no, I am one of them), I mean, each compute node, may contain one or more sockets. There are different names for the same thing, but a socket is equivalent to a CPU on a consumer PC or laptop. Essentially, each socket will contain a number of so-called cores, or processors. On a consumer PC, we may have a 4-core CPU, but in HPC land, we typically have quite a few more per socket, starting at 16 cores, and going up to 64 or even 128 cores.

Let’s look at some real examples. The figure below shows a typical HPC cluster, as you may find it in the wild.

Again, whoever is setting up HPC clusters seems to spend a lot of effort on making HPC clusters look sexy. Some will plaster wallpapers all over the place, some will install mood lighting, and how is this different from a script kiddie spending way too much on LED lights for their gaming PC?

The more I think about it, people working in HPC are just grown-up kids. And after this thought entered my mind, I just couldn’t stop thinking that everyone in the Harribo commercials is just someone working as an HPC admin. I mean, how is the following not an annual meet-up of HPC admins?

Congratulations, you just watched an advert, and no, of course I’m not getting paid for this (did you really think Harribo is sponsoring me?). Moving on.

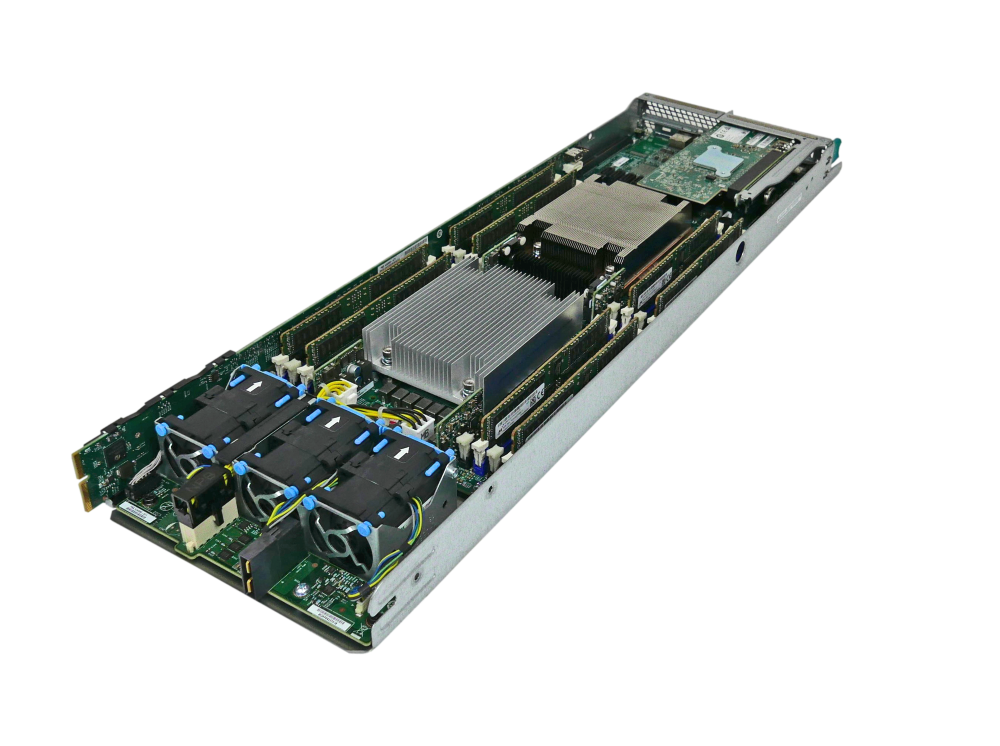

Within each cabinet, we have our racks, each stuffed with compute nodes, and this is shown below:

If you click through to CTO servers, you’ll see that this beauty is sold as a stand-alone OpenFOAM HPC cluster. And I may add, looking at the specs, it is very reasonably priced … I might get one for myself … (I’m not, (and, no, again, not getting paid to promote them either, just think this is a cool product, but I love bare metal hardware, you can sell me anything)).

If we take one of the compute nodes out of the rack, we start to see hardware that finally resembles a consumer PC or laptop. This is shown below:

Here, we have two sockets in the centre, both shielded by a metallic heat exchanger device. Each socket may contain 16, 32, 64, or 128 cores, typically, and so if we have two of these sockets per node, we may end up with a total of 32, 64, 128, or 256 cores per node. That is some serious computing power! To either side of the sockets, we have our main memory (RAM), and we have some fans at the bottom.

Other compute nodes may additionally house a small GPU as an add-on, though we can also get entire GPU nodes. If you want to have some fun, google “what is the most expensive Nvidia GPU”. At the time of writing, the H100 is still leading the market with its ~£30,000 price tag. For the same money, you can almost get a Tesla Model S, and I am sure we are not far away from Nvidia’s GPU becoming more expensive than electric cars.

I mean, at this rate, we may see celebrities start to wear Nvidia GPUs as status symbols instead of jewellery or fashion brands. Me: “Create a picture of a celebrity of your choice wearing a Nvidia GPU like a status symbol”. ChatGPT:

There are three possibilities for how we can create our HPC system. Either we have a homogeneous system, using only CPUs or GPUs, or we have a heterogeneous system, having a mix of CPUs and GPUs. Most HPC systems these days are heterogeneous and cater for both CPU and GPU applications, though you will find more and more dedicated GPU clusters, which are predominantly used for AI, so we can create a pointless cartoon impression of celebrities wearing GPUs as status symbols.

Another important aspect of HPC clusters is their network. Nodes and cabinets are typically connected through a very high-throughput and low-latency network. A common choice here is the InfiniBand standard. As we will see, in most of the cases we are interested in (SIMD CFD applications), our bottleneck is memory transfer, and we spend a lot of effort squeezing the last bit of performance out of our code by placing the data as close as possible next to each other to reduce memory transfer time.

There are different mechanisms by which we can achieve that, and we will look at them later in this article. But for now, I think we have gotten a good overview of the HPC hardware and architecture. Let us now explore how we can measure performance in our codes, some bottlenecks for our performance, as well as some considerations that are less commonly discussed in the HPC literature.

Performance and bottlenecks

OK, so we have access to a few cores now, either through our CPU on our laptop/PC, heck, even our smartphones these days come with an 8-core CPU (this will age like milk …), we want to leverage them. We may even have access to a decent cluster, and we may be able to use a few hundred cores, for example. Should we always use all of the computational resources we have available?

For each simulation we run, there is an optimal number of cores, and so we want to know at which level of parallelism (i.e. how many cores) we get the most performance (reduction in computational time). Beyond that point, we will start to increase the computational cost (i.e. we use more cores, requiring more energy), and the performance will decrease (increase in computational time).

Thus, we want to find out what the optimum number of cores is. There is no one-size-fits-all answer, and the optimum number of cores is a code-specific number. But there are ways in which we can establish that numerically, and so in this section, we will look at this in more detail.

The optimum number of cores is not the only thing we want to look at, though, even though the answer may be that we should be running our simulation on 128 cores for 2 days, we should ask ourselves if we really need to. Do we need to run this simulation? This question seems odd, and is probably never asked, but once we look into the economics of running large-scale simulations, we realise that we are quite heavily polluting the atmosphere with CO_2.

So the question: “Are we getting enough information out of this simulation to justify the electricity usage and CO_2 release” becomes a relevant and highly important question.

For example, if we want to run a Large Eddy Simulation (LES) around an airfoil at various angle of attacks, just to get a better prediction of the critical (stall) angle of attack, compared to a much cheaper Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) simulation, we should calculate the expected electricity usage and CO_2 release for both cases and make a judgement on whether we can justify the cost for obtaining a single value with a somewhat improved predictive quality.

We may come to the conclusion that no, it is not justified, and that perhaps other approaches can be explored. For example, we can create a 2D RANS mesh with a lot more resolution than our 3D LES grid and get a transitional RANS model to predict the stall angle with perhaps a slightly less accurate prediction, but with a significantly reduced computational cost.

These trade-off considerations are not commonly done. CFD practitioners are not seeing the energy bill, nor do they see any environmental reports on how their HPC usage contributes to their CO_2 footprint.

I bring this up because I generally observe a lack of awareness in my students when they run a simulation. They get upset when they can’t run as many simulations as they want for their MSc thesis, but then run simulations on the cluster that fail after some time because they were not thoroughly tested. Sometimes these simulations don’t even add value, and so my original question, “Are we getting enough information out of this simulation to justify the electricity usage and CO_2 release” is not that strange after all and highly relevant!

Let’s now discuss a few metrics we can use to assess the parallel performance, and then circle back to the environmental considerations afterwards.

Amdahl’s law

Amdahl’s law is a simple yet very educational law we can use to assess parallel performance. It is so simple that it is easy to understand, yet it gives us some surprising results, especially if we have never seen it before.

Let’s think about parallelism for a moment. Our goal is to use more than one core in the hope that our simulation time will reduce proportionally to the number of cores that we are using. As a simple example, we may say that a simulation may run exactly for 32 minutes using a single core. Then, if I use 2 cores, I would hope that my simulation only takes 16 minutes. If I use 32 cores, I would hope that my simulation only takes 1 minute. That is parallelisation in a nutshell.

But there are things which cannot be parallelised. For example, if I run on 32 cores and I want to print something to the console, like my residuals, or some information about the current time step, like the timestep size and total elapsed simulation time, only one processor will do that. If all 32 processors did that, we would get the same information printed 32 times.

Writing data to the hard drive is another aspect that is difficult to parallelise, although there are non-trivial options to do this with MPI I/O and HDF5, for example, it is a task that may also be done by only one processor. So, there will always be some portion of the code that cannot be parallelised, and we will never get a code with 100% parallelism.

How could we express that mathematically? Let’s say that T is the total time it takes to run our simulation, so 32 minutes on 1 core, 16 minutes on 2 cores, and so on. Then, we can introduce two additional times. T_{par} is the execution time of the code that can be parallelised, while T_{no-par} is the part of the code that cannot be parallelised (writing to the console, or hard drive, for example). Thus, the total time is:

T=T_{no-par} + T_{par}

\tag{1}

So far so good (and simple). Now, let us try to express T_{no-par} and T_{par} as functions of T alone. For that, we will introduce a fraction f that is in the range of [0,1]. A value of f=0.8, for example, would say that 80% of our code can be parallelised. The way we could determine that, for example, is to go through each line of our code and see if it is executed in parallel or not. Then we may have 80 lines of code that run in parallel out of 100 lines of code, so f=80/100=0.8.

We can now start to weight the contributions in Eq.(1) with:

T_{no-par} = (1-f)T\\

T_{par} = fT \\

T = (1-f)T + fT

\tag{2}

So, we have now found a way to express the total computational time as a weighted sum of the parts of the code that can be parallelised and that cannot. Let’s now also consider the speed-up s. This is the factor by which we reduce our computational time after parallelising our code. Let’s make the example simple. Let’s say f=1, so everything can be parallelised. Then, we have:

T=fT\tag{3}If we wanted to compute the speed-up, we would have to divide the right-hand side by s, i.e. we get:

T=\frac{f}{s}T\tag{4}Now, we can say f=1, so if we use 32 cores for our 32-minute simulation, we get:

1\, min=\frac{1}{32}32\, min\tag{5}But now let’s extend that for cases where f isn’t 100%. So we bring back our weighted sum from Eq.(2). This results in:

T = (1-f)T + \frac{f}{s}T

\tag{6}

We do not divide (1-f)T by s because that is, by definition, the part of the code that cannot be parallelised, and so we cannot speed up this part of the code. Therefore, only the part that can be parallelised will benefit from the speed-up.

Eq.(6) will give us the time it takes to run our simulation on p processors. We can denote this time by T(p,f), where we also include the fraction of the code that can be parallelised, i.e. f. Thus, Eq.(6) becomes:

T(p,f) = (1-f)T + \frac{f}{s}T

\tag{7}

Remember that T is the total time it takes to run the simulation. On a single processor, this would be T(1,f) = T by definition, because there is nothing to parallelise on a single core (we could also say that f=0). This would give us the same result, i.e.:

T(1,f) = (1-0)T + \frac{0}{s}T = T\tag{8}If we wanted to know the speed-up as a function of the fraction of the code that can be parallelised, i.e. f, we compute the ratio of T(1,f)/T(p,f). This results in:

\frac{T(1,f)}{T(p,f)} = \frac{T}{(1-f)T + \frac{f}{s}T}

\tag{9}

We can simplify this equation as:

\frac{T(1,f)}{T(p,f)} = \frac{T}{(1-f)T} + \frac{T}{\frac{f}{s}T} = \frac{1}{1-f}\frac{T}{T} + \frac{1}{\frac{f}{s}}\frac{T}{T} = \frac{1}{1-f} + \frac{1}{\frac{f}{s}} = \frac{1}{(1-f) + \frac{f}{s}}

\tag{10}

This is an important finding, so let me write the final result again so it stands out better:

\frac{T(1,f)}{T(p,f)} = \frac{1}{(1-f) + \frac{f}{s}}

\tag{11}

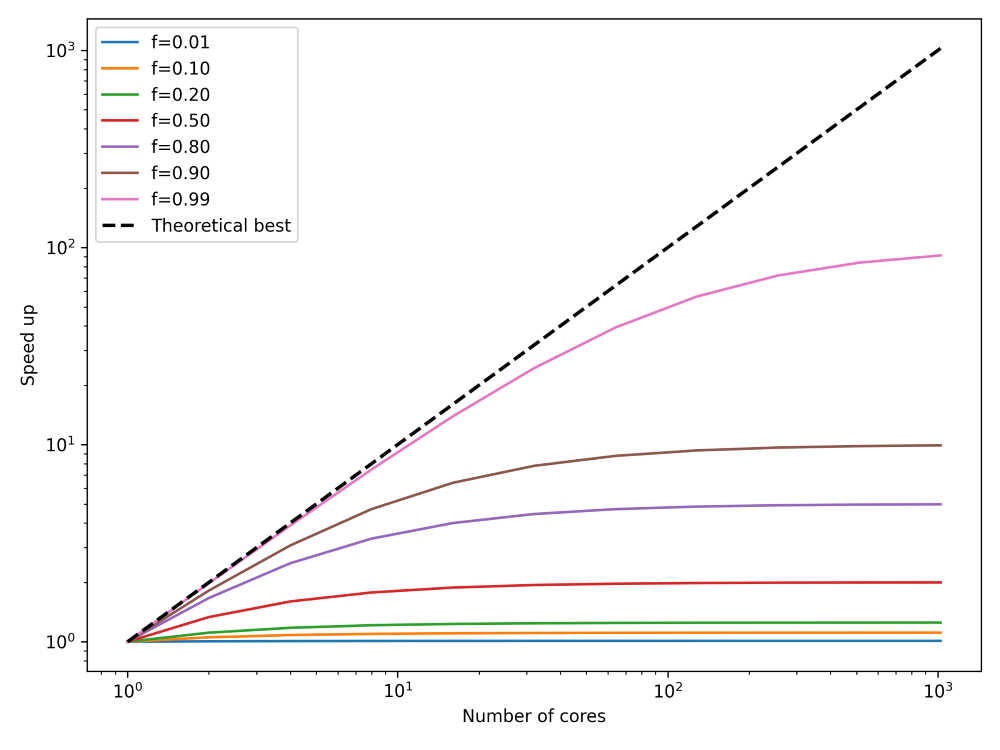

This is Amdahl’s law, and it tells us that we can compute the theoretical speed-up knowing only the portion of our code that can be parallelised f and the speed-up s. We can use this to determine upper bounds for our parallelisation efforts. This is shown in the next figure:

What I have done here is to plot the speed up, on the y-axis, we can expect for any number of cores, given on the x-axis. I have also plotted the theoretical best parallelisation, that is, if all of our code can be run in parallel. This is shown as the theoretical best line, and this corresponds to f=1. I have plotted how our speed-up converges to a fixed value, regardless of how many processors we are using (we are assuming here that the speed-up s is proportional to the number of cores).

Thus, we can see that there are diminishing returns if we use more and more processors, and we can even compute the upper bound with Amdahl’s law, what the best performance s_{opt} is that we can expect. To do that, we have to compute:

s_{opt} = \lim_{s\rightarrow \infty}\frac{1}{(1-f) + \frac{f}{s}} = \frac{1}{1-f}\tag{12}Thus, the best speed up is determined not by the part of the code that can be parallelised, but rather by the part that cannot be parallelised, which is 1/(1-f). So, we can find s_{opt} numerically for different values of f as:

- f=0.01 \rightarrow s_{opt} = 1.01

- f=0.10 \rightarrow s_{opt} = 1.11

- f=0.20 \rightarrow s_{opt} = 1.25

- f=0.50 \rightarrow s_{opt} = 2.00

- f=0.80 \rightarrow s_{opt} = 5.00

- f=0.90 \rightarrow s_{opt} = 10.00

- f=0.99 \rightarrow s_{opt} = 100.00

This means that the number of cores we have available is not really important. Much more important is how well our code has been parallelised. Even if 99% of our code can execute in parallel, we can expect, at best, a speedup of 100. So, if we have access to, say, 1000 cores, we wouldn’t be able to use all of them. We would be limited by the theoretical speed-up of 100, at most. In order to use all 1000 cores, we would first have to ensure that we have at least 99.9% of our code parallelised.

These numbers may seem frightening, but in reality, it isn’t that difficult to achieve parallelisation of 99.9% or even more. Look at scientific articles where people run their simulations with 10,000 cores or more successfully, i.e. seeing a corresponding speed-up. It is possible.

Having said that, I should also state that we like to cheat a bit in CFD (everybody is doing it, so that makes it Ok, right?). We typically ignore large portions of our code, and only measure the part of the code that has been parallelised. Things like reading a mesh, allocating memory, etc., are not considered. We only look at our time or iteration loop, which can, in general, be easily parallelised. This is where most of the computational time is spent, which justifies this approach.

The takeaway message is that Amdahl’s law tells us that we cannot just throw an infinite number of processors at our problem; eventually, we will reach a ceiling beyond which we cannot expect more performance.

Amdahl’s law is a good theoretical model to sensibilise ourselves to the fact that there are diminishing returns as we increase the number of cores. However, in reality, it is very difficult to know what the fraction f is of our code (it turns out, just counting the lines of code isn’t a reliable indicator, and even worse, if we have 1 million lines of code or more, who’s got the time to do that?).

So, we need a different metric that embodies the same information as Amdahl’s law, but we can access that information by just measuring the performance of our code. This is where weak and strong scaling come in, and these are discussed in the next sections.

Strong scaling

The strong scaling measures the speed-up of a parallel code execution. We keep the problem size the same and only change the number of cores. We want to measure how the speed-up changes as we increase the number of cores. We can define the speed-up as:

s(p) = \frac{T(1,N)}{T(p,N)}

\tag{13}

We use a slightly different notation here compared to the previous section. Here, p is the number of cores we are using, just as before, but N is now the problem size. In our case, it would typically be the number of cells in our mesh. If we are dealing with a finite element discretisation, N would be the number of degrees of freedom (since we can have more than a single integration point per cell). Regardless of which approach we chose, N is always proportional to some characteristic size we can state about our problem.

The time it takes to run the simulation on one core is given as T(1,N). The time it takes to run the simulation on p cores is T(p,N), and the ratio of the two gives us the speed-up, as seen in Eq.(13). Let’s look at some sample numbers, which were taken from HPC-wiki. The table below shows typical numbers you may find when you measure the execution time of your code as you increase the number of cores.

| Number of cores (required nodes) | Measured time (in seconds) |

|---|---|

| 1 (1 node) | 64.4 |

| 2 (1 node) | 33.9 |

| 4 (1 node) | 17.4 |

| 8 (1 node) | 8.7 |

| 16 (1 node) | 4.8 |

| 32 (1 node) | 2.7 |

| 64 (2 nodes) | 1.6 |

| 128 (4 nodes) | 1.0 |

| 256 (8 nodes) | 1.4 |

| 512 (16 nodes) | 3.7 |

| 1024 (32 nodes) | 4.7 |

| 2048 (64 nodes) | 21.5 |

In the left column, we see the number of cores required, as well as how many (compute) nodes we need. In this case, each compute node has 32 cores. On the right, we show the measured time it took to run a given simulation on the given number of cores.

We need to be careful how we obtain these time measurements. We can’t just go to our cluster, run a simulation for a number of cores, record the time, and then move on. If we do that, we will get a lot of noise, or variance, in our results. Instead, we should run the same simulation over and over again. With a number of measurements available, we can now either compute the average time or take the shortest time. I have seen both approaches being used in the wild.

When CPUs are not in use, they are typically underclocked to save energy. So, if you throw your simulation onto a compute node that was idling for some time before you showed up with your (simulation) problems, it is likely that the process of bringing the compute node back up to speed will influence your measured compute time. In this case, we may want to give the compute node a task to do for a few seconds before we start measuring simulation times.

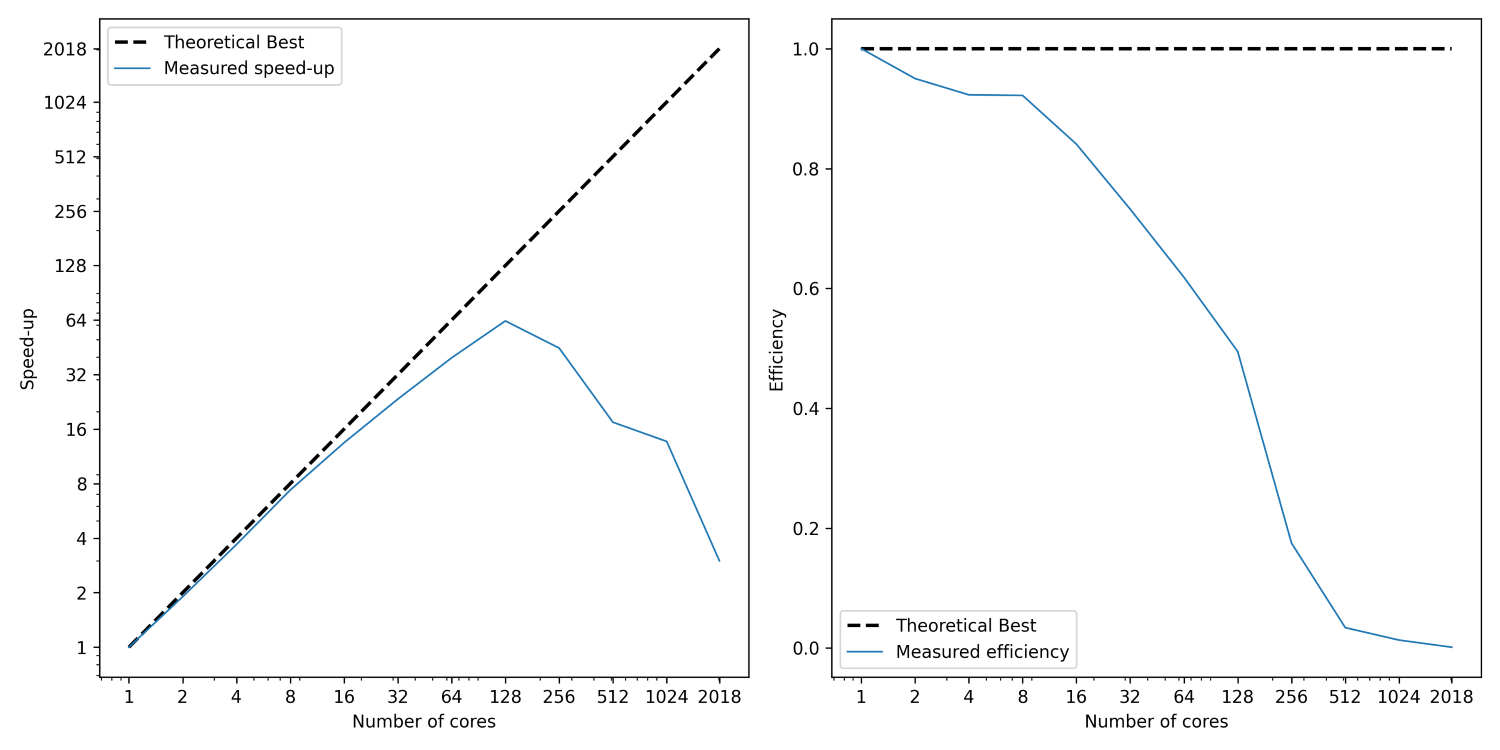

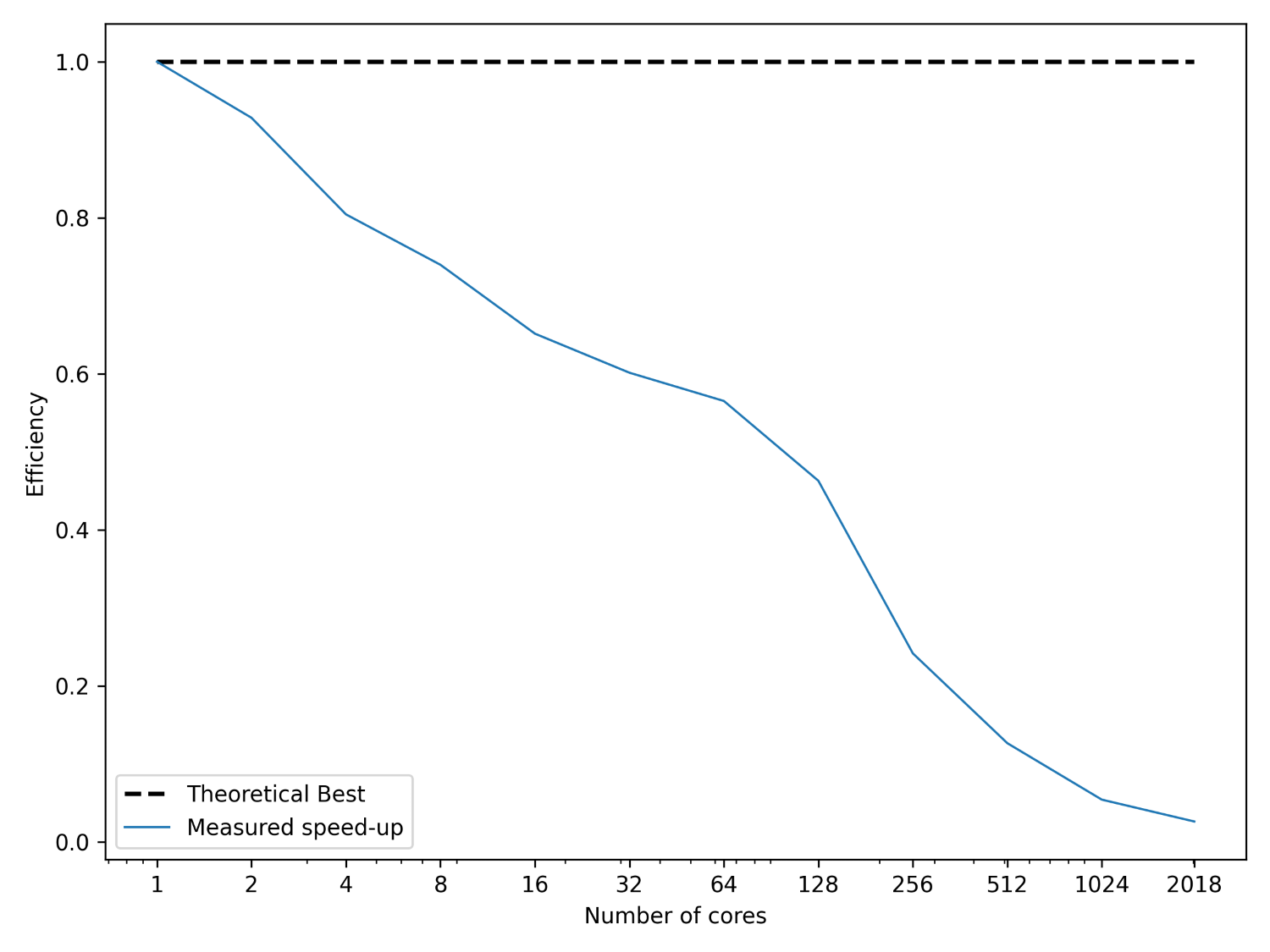

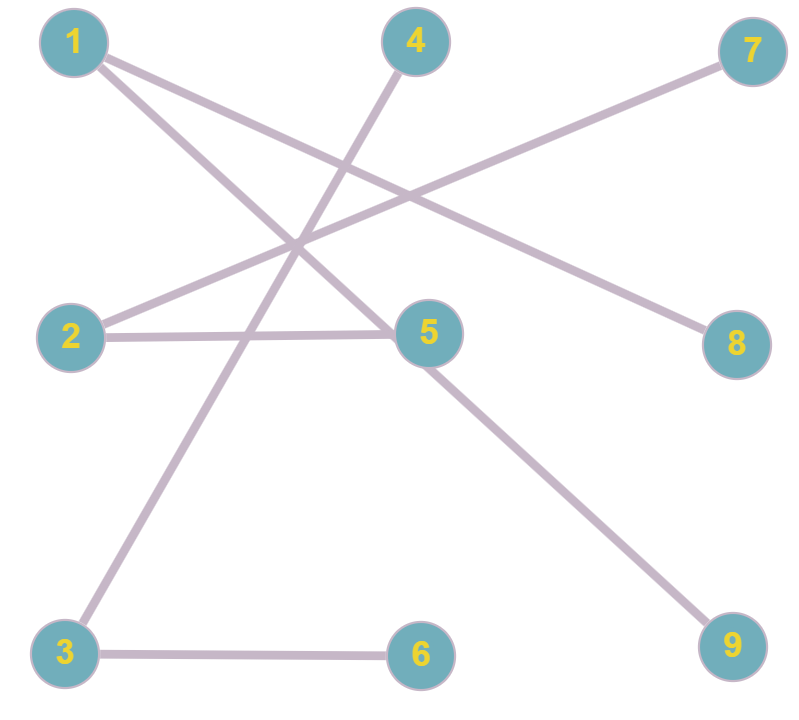

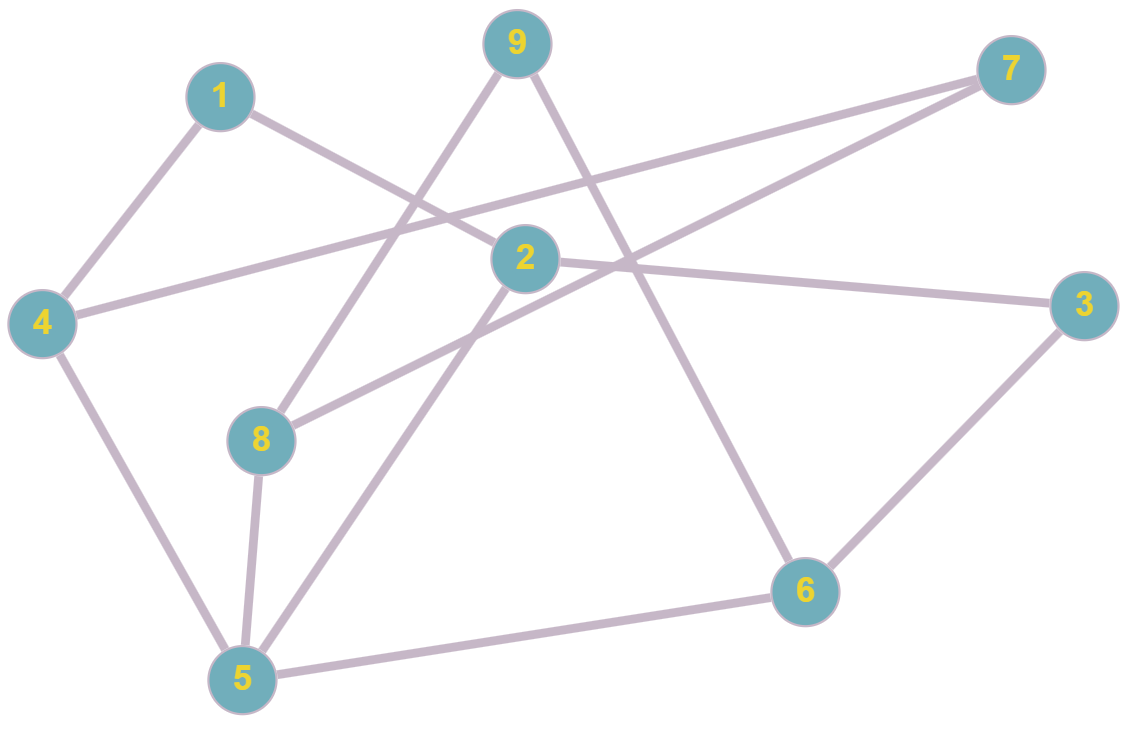

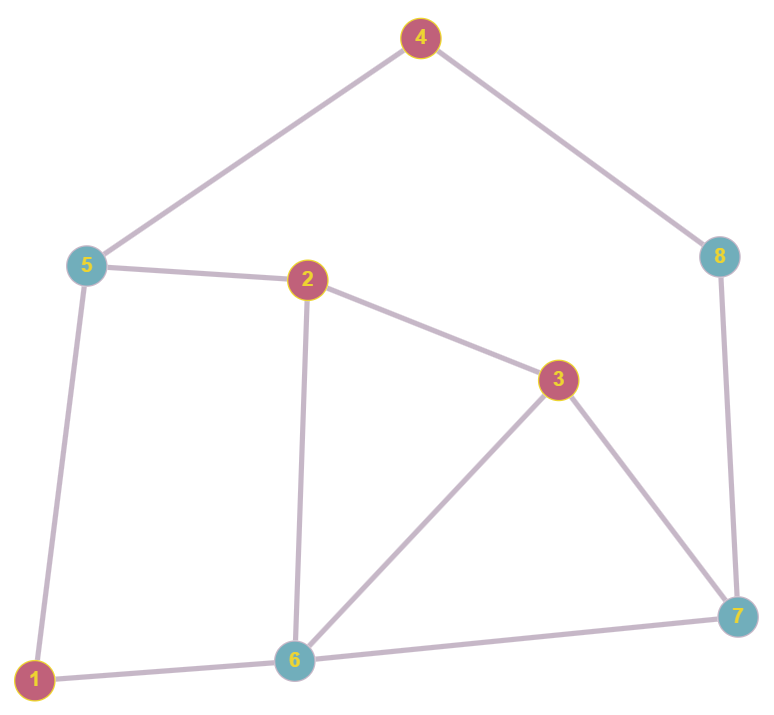

If we compute the speed-up now based on the time measurements we saw above in the table, then we can plot it against the number of cores. This is shown in the figure below on the left:

I have shown here two lines; the first (dashed) line shows the best possible speed-up. That is, if we use p processors, then a speed-up of p is the best possible scenario we can expect. While we see that the measured speed-up, shown as a solid blue curve, follows this trend initially, it starts deviating from it relatively soon. At around 128 cores, we see a peak. Afterwards, the speed-up is going down again.

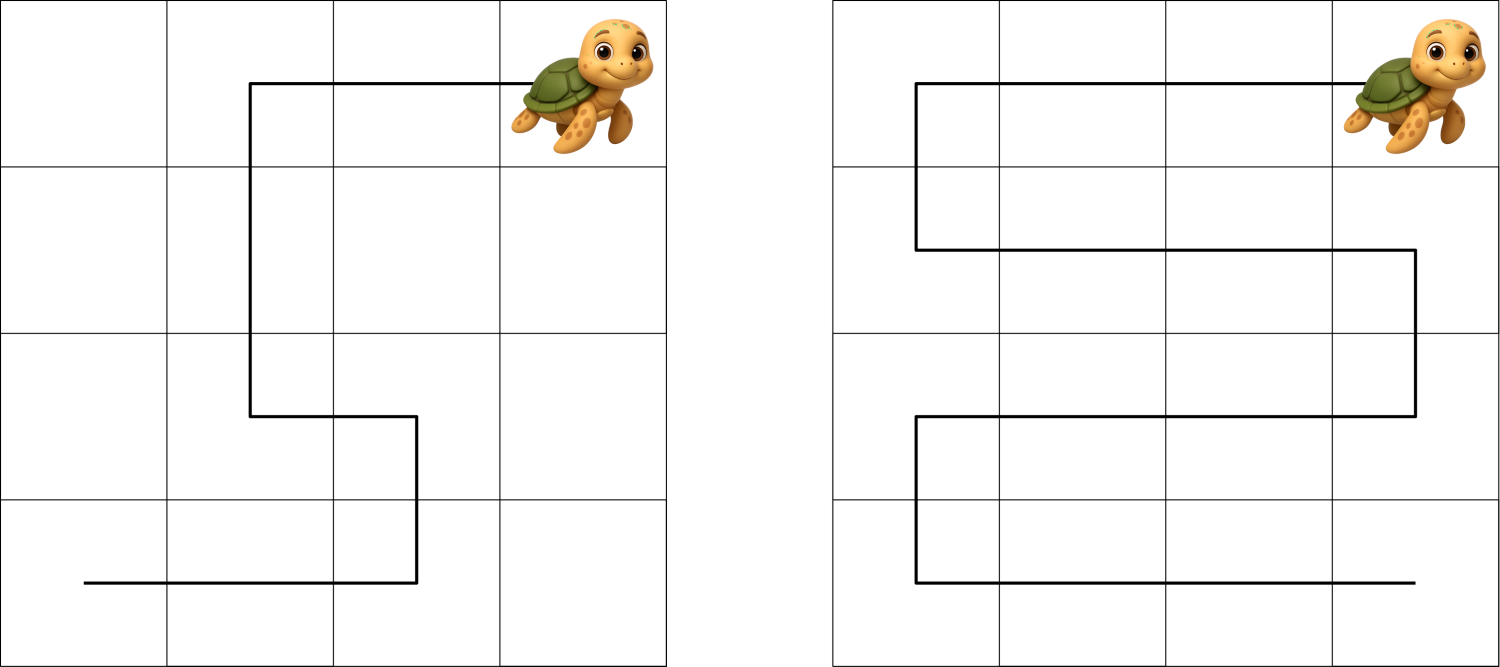

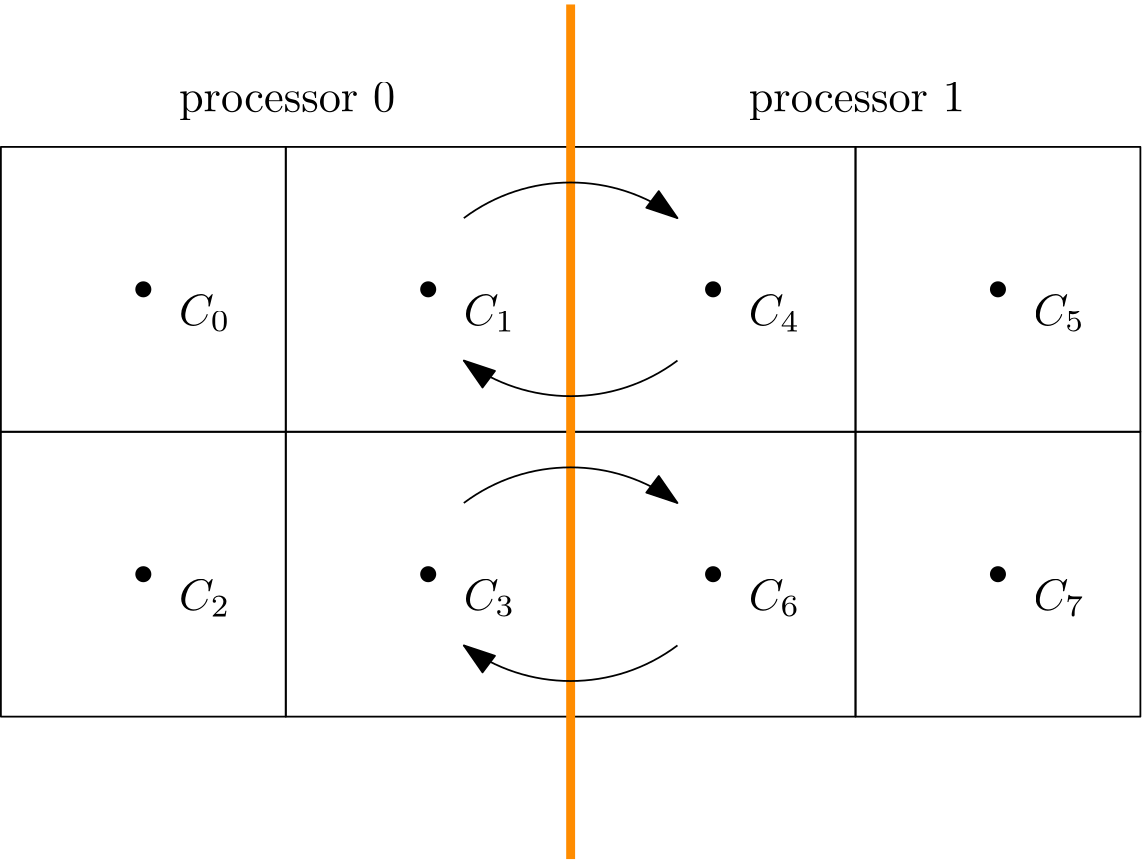

This is the expected behaviour. In order to understand that, we need to know more about how code parallelisation works (and we will look at that in more detail). But in a nutshell, imagine we want to compute the gradient of the velocity field in the continuity equation. Thus, we may have a finite difference approximation as:

\nabla\cdot\mathbf{u}=\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial v}{\partial y} + \frac{\partial w}{\partial z} = 0\\[1em]

\nabla\mathbf{u}\approx \frac{u_{i+1, j,k} - u_{i-1,j,k}}{2\Delta x} + \frac{v_{i, j+1,k} - v_{i,j-1,k}}{2\Delta y} + \frac{w_{i, j,k+1} - u_{i,j,k-1}}{2\Delta z} = 0\tag{14}Let’s look at u_{i+1, j,k} and u_{i-1, j,k}. We said before that in order to achieve faster code execution, we may split a 10-million-cell problem over 4 processors, where each processor is now solving only a 2.5-million-cell problem. This means that our original mesh is now chopped up into smaller chunks. But, if we compute the solution near or at the boundary of one of these subdomains, then we may find that u_{i+1, j,k} is still on our domain, but u_{i-1, j,k} isn’t.

It turns out that u_{i-1, j,k} is on the neighbouring subdomain, and so we have to request now a copy of that from our neighbour. So, we send a request, and we wait. Imagine you need a vital piece of information, but you don’t have it. But, you know who has it. So, you may send that person an email and wait for their response. Once they get back to you, you can continue to work, but in the meantime, you are waiting for a response before you can continue.

The same is true for our request to get data for u_{i-1, j,k}. Even though the communication is instant, it has to go through the network (or, if the data is close to us, through the CPU), but one way or another, we have to copy memory around. As we saw in the computer hardware section, accessing memory is costly and much slower than the speed of our CPUs.

Thus, a bit of communication is fine, and we can hide it behind the work we are doing on our CPU. But there is a point where communication will become so costly that it dominates our simulation. At that point, we no longer see a speed-up, but rather, a slowdown. This is what we are seeing in the left figure above. Using more than 128 cores will slow down our simulation again.

Since we keep the problem size the same, i.e. let’s say we use 10 million cells, as we use more processors, the subdomain that each processor works on becomes smaller and smaller. If we have 1 processor, then it will work on 10 million cells; if we have 2, each will work on 5 million cells; if we have 4, each processor will work on 2.5 million cells, and so on.

So, with an increase in the number of cores, we have a decrease in the problem size and thus less computational work to do per core. But, with an increase in the number of processors, we also have an increase in communication (we now have more processors talking to each other). There is a point where there is no more speed-up, as we are not spending enough time on computing but rather on waiting for communications to finish.

Another measure that we commonly compute is the efficiency. This is given as:

E(p, N) = s(p,N) / p

\tag{15}

The efficiency checks the speed-up for a given number of processors. Say we get a speed-up of 8 using 10 processors, then, if we divide that by the number of processors (10), we get an efficiency of 8/10 = 0.8, or 80%. The ideal speed up would be 10 instead of 8, and so the efficiency measures how far we are away from the ideal speed-up. This is computed and shown in the figure above on the right.

If we now take what we have learned on Amdahl’s law and strong scaling, it may seem that we are doomed. No matter what we try, it appears that there is no way to efficiently use a large number of cores. To a certain extent, this is true. Yes, it is difficult to make a code as efficient as possible in using parallel resources. For this reason, you will find commercial CFD solver developers spending a lot of effort in improving their parallel code performance.

However, there are lots of ways in which you can cheat with your strong scaling results and make it look really efficient, when in reality, it is not. Academics seem to be among the worst offenders, either due to incompetence (not understanding the limit of strong scaling results) or just being mischievous.

The first thing we have to set is a baseline problem with strong scaling. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that we get the highest speed-up when we have 100,000 cells per core. If we add more processors, we get fewer cells per core, and so we see a slowdown. If I now set my baseline problem on which I investigate my strong scaling to be 1 million cells, then I will see my strong scaling results indicating that 10 cells is ideal. If I use more than 10 processors, my performance will decrease again.

However, if my baseline problem is 10 million cells or even 100 million cells, then the optimal number of processors is 100 or 1000, respectively. The quality of my strong scaling results is only as good as my pain tolerance to wait for that first simulation to finish. Remember, on 1000 cores, running a 100 million cell simulation is fast. But on 1 core, it will be, well, about 1000 times longer. If I can afford to wait days for the simulations on a single core to finish, then I get excellent strong scaling results.

Thus, the strong scaling itself is not very informative; what we also should always report is the problem size, so that we can work out how large the problem is per core at its optimum. Knowing this number is far more important than the strong scaling result itself; however, even this number can be tampered with and made arbitrarily small.

For example, commercial codes typically can go down to 50,000 cells per core. If you reduce the problem size further, you will lose performance. Open-source CFD solvers can go down to about 100,000. Well, these are some experiential values, and your experience may differ, but as an order of magnitude guestimation, these values are good to remember.

However, above we said that the problem with decreasing the number of cells per processor is problematic because we don’t have enough computations to do, and so the time we wait for communications becomes the limiting factor. We can exploit that and just make our code perform more computations than are necessary. In this way, we have again enough computations to perform, and so we can reduce the number of cells per processor before it becomes less efficient again.

I have seen a code where each computation per cell was done twice. Not due to malicious purposes, i.e. showing impressive strong scaling results (although the authors of the code also did that), but rather due to laziness. It was easier to perform the computation twice, as this would allow for a simpler data structure in the code. Thus, from the outset, the code was slow to begin with (a code with an optimised data structure would likely be twice as fast).

So, when it came to parallelising this code, they would see pretty good strong scaling, and they would get close to commercial solvers in terms of how many cells per core would be an optimum for their solver. By artificially increasing the number of computations you have to do, of course, you get a lower number of cells per core as the optimum, but this behaviour is no different to lying on your tax returns (which, last time I checked, is illegal).

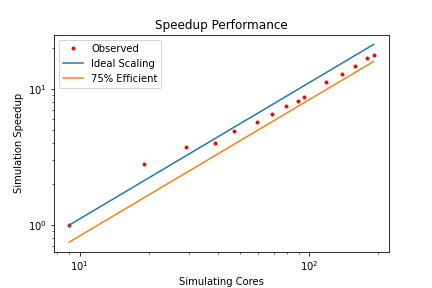

But there is one more thing we need to discuss, and that is something that may be difficult to grasp, or perhaps put down to as a measurement error, when in reality, a perfectly good explanation exist. Take a look at the following plot:

First of all, these strong-scaling results are shown as a log-log plot, while we used a semi-log plot thus far, so it will look slightly different (it is more common to use the semi-log plot that we have used before). But have a closer look at the measurements, what is going on with the second and third measurements? This is not a measurement error, and it is not the result of averaging measurements or manipulating them in some other way. The speed-up we are seeing is real.

But how can we get a speedup that is larger than the theoretical best performance? In other words, if we have, say, a speed up of 2.2 for 2 cores, then our efficiency, according to Eq.(15), is E=2.2/2 = 1.1 = 110%. We have an efficiency that is greater than 1, or 100%, something seems to be off here. But let’s look at our computer hardware a bit closer:

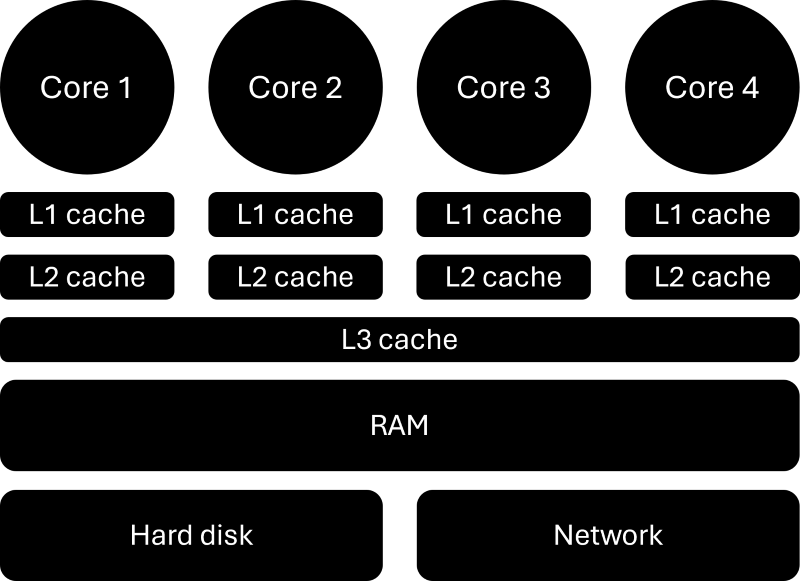

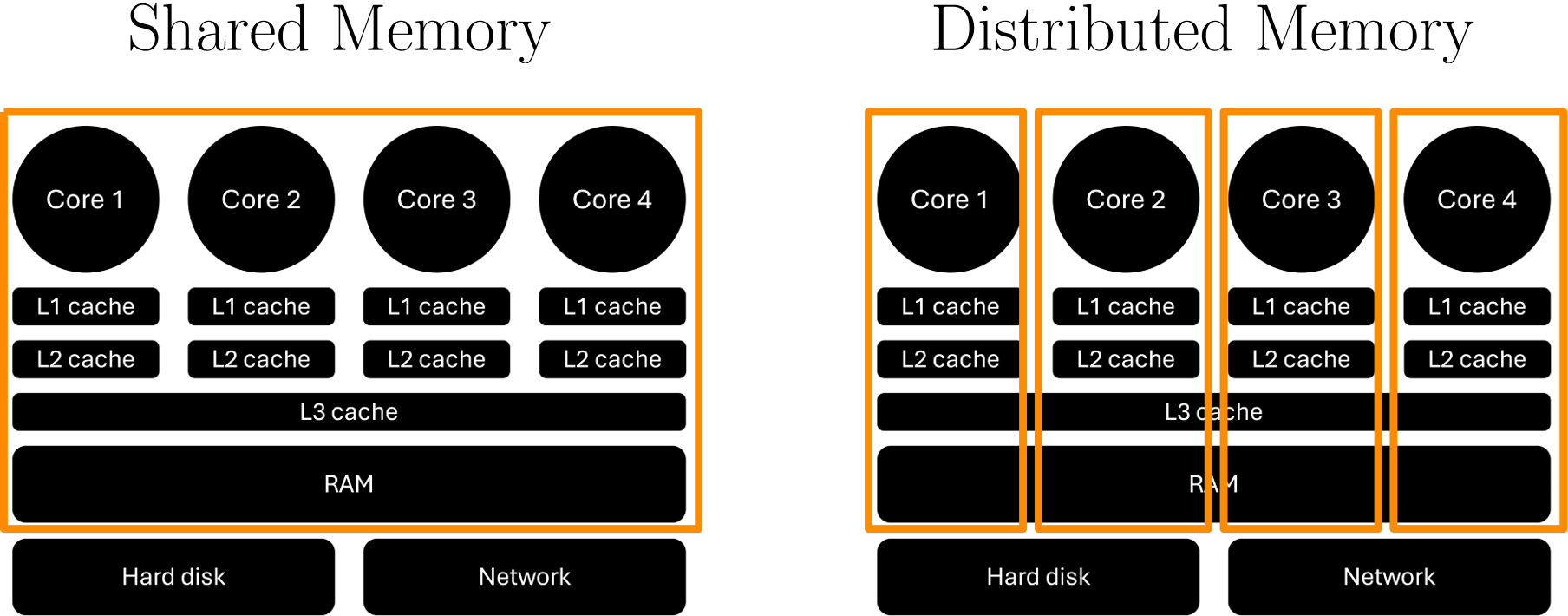

As we have discussed, a CPU consists of several cores, or processors, but they also have a number of caches, typically three levels. The L1 and L2 (level 1 and level 2) caches are sitting next to each core and are local to that core, but the L3 (level 3) cache is shared among all cores on the CPU. When data is required from main memory (RAM), the CPU will request the relevant data to be copied into the L3 cache. Each core will then take from that L3 cache what it needs and put that into its L2 and L1 cache.

The reason we do that is speed. The CPU is so fast that if we were to always read memory directly from main memory (RAM), it would take so long that most of the time the CPU would be waiting for memory. The solution is caches. It is the same reason we do grocery shopping. When we want to cook, we don’t go to the supermarket and buy the stuff we need, but rather get a bunch of ingredients upfront and then, when we want to use them, we go to the fridge and food cupboard and get what we need.

In this analogy, the supermarket is RAM, and our fridge/food cupboard is our cache. When we need memory, the CPU requests data and places it in the L3 cache so each core can use it, which is equivalent to us going to the supermarket and getting a bunch of things which we can store at home so they are there when we need them. While the supermarket has so much capacity that it has pretty much anything we could ever need, our fridge and food cupboard have limited space.

The trade-off, thus, is the capacity for access speed. I can get anything I want in the supermarket, but it will take time to get it. But if I can get what I need from my fridge or food cupboard, it is there, and access time is basically zero. The same is true for RAM and caches. Accessing memory from RAM is slow, but accessing memory from our caches is fast. In the case of L1 caches, it can be as little as a single clock cycle (which means our CPU has the data available when it needs it and doesn’t have to wait for it).

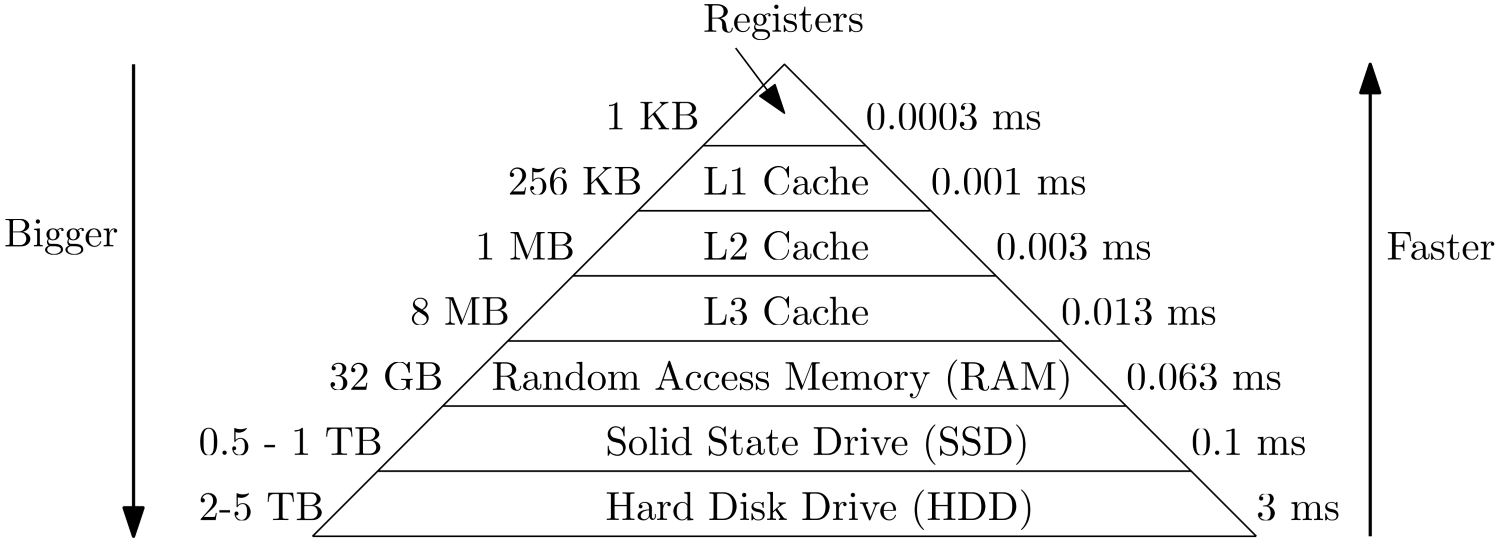

The following figure shows access times vs. capacity for different memory modules, which helps to illustrate this point. Note that these numbers are approximate, so the order of magnitude is more important than the absolute value.

The CPU will only work with registers, which are sitting next to each core. Their data is coming from the L1 cache, and so on. We can see that the smaller the memory modules are in capacity, the faster they can load memory. The reason is that memory needs to be indexed, which can take time. If you park your car in a parking area that takes 20 or 2000 cars, in which of these parking areas will you, on average, find your car quicker? The smaller the parking area, the faster the access time, and the same is true for memory.

So, how does all of this relate back to our strong scaling results? Well, let’s use the figure above and see what happens if our baseline simulation consumes 2 MB of storage. Arguably, this is a very small problem, but let’s go with this example. We run this example on 1 core and, because this problem is so small, it does fit entirely into our L3 cache. No need to go to main memory.

We now perform our strong scaling measuring campaign and realise that for 2 and 4 cores, we get an efficiency of more than 1, or 100%. The reason here is that we split our original 2 MB problem now amongst 2 and 4 processors. Thus, each processor will get a problem size that is now either 1 MB or 0.5 MB, respectively. Looking at our memory hierarchy above, we can see that this is now just about small enough so that the entire problem fits into the L2 cache.

Since the L2 cache has faster access times than the L3 cache, we do see a speed-up that goes beyond the predicted theoretical best. What we have to realise here is that the theoretical best performance was predicted based on the single-core simulation, which took place in the L3 cache. But once we break down our problem, eventually it will fit into smaller caches, where the theoretical best speed-up is different.

However, since we compare our results against the theoretical best based on the single core simulation, we can get efficiencies that are above 1, or 100%, i.e. we see speed-ups that go beyond what is theoretically possible. This behaviour is called superlinear scaling, or superscalability, and is just a consequence of our memory hierarchy.

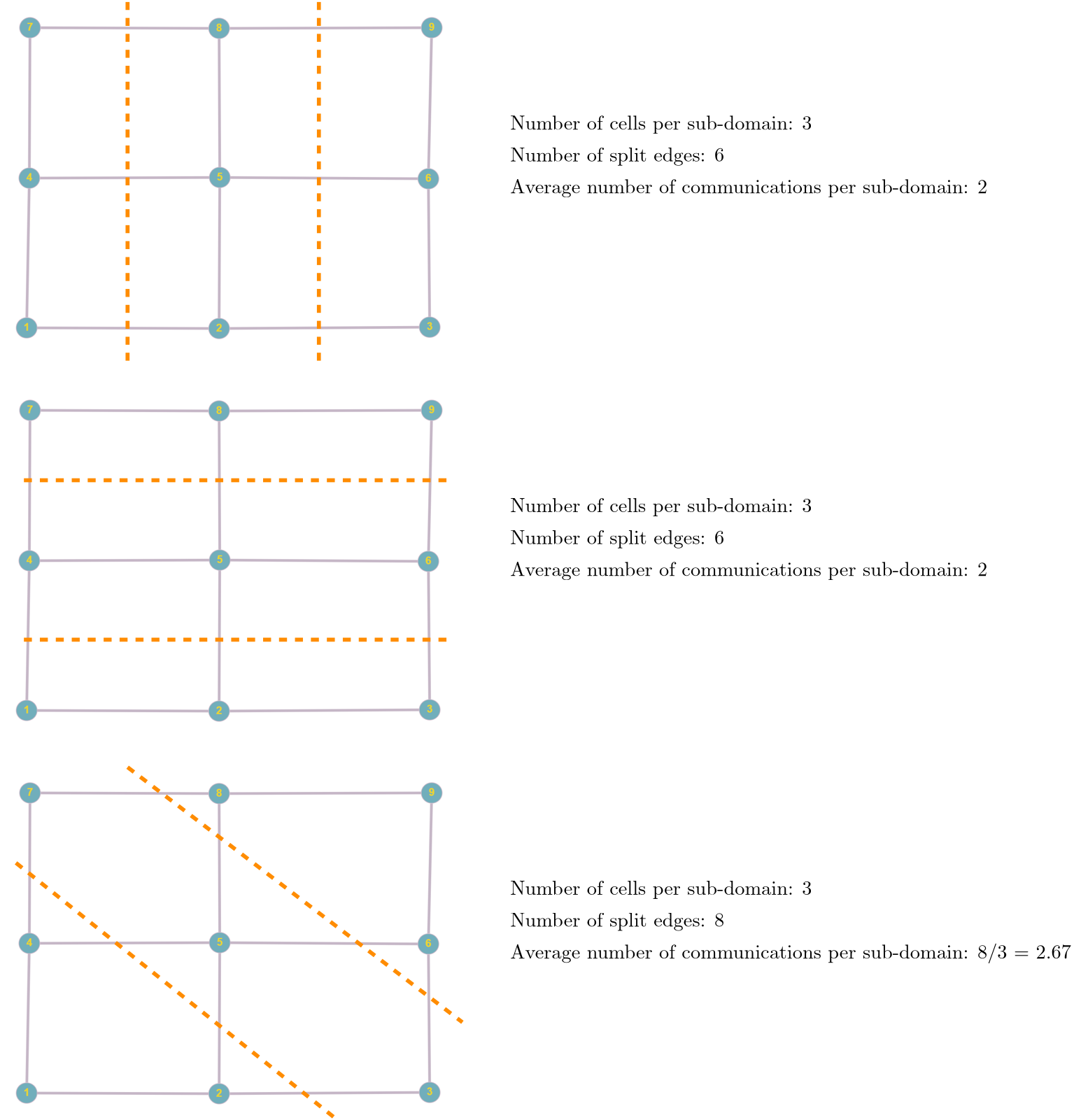

Weak scaling

In strong scaling, we took a fixed problem size (e.g. the number of cells in the mesh) and measured the speed-up for an increasing number of processors. This meant that the problem size per processor was getting smaller and smaller as we increased the number of processors. In weak scaling, on the other hand, we keep the problem size per processor the same.

So, if we simulate a problem of 1 million cells on a single core, then, in weak scaling, we would have to use a problem size of 2 or 4 million if we measured their weak scaling for 2 or 4 processors, respectively. The question then becomes, why would we do that? If we keep the problem size the same per core, we would expect to see the same computational times, or not?

Let’s think about what happens when we increase the number of processors. Initially, we only use a single core. Even if we increase the number of cores to a handful, we are likely still on the same compute node. As we increase our number of cores, we start to use more than a single compute node. If we increase the number of cores even further, we will start to use compute nodes that are further apart in space.

At first, these compute nodes are within the same cabinet, but then, as we use more and more cabinets, our communication has to go through the network, which is now separated in space. The further apart these compute nodes are, the longer it takes to send data over the network.

Consider this: HPC clusters use optical (glass) fibres in their network. This allows them to send data at almost the speed of light, i.e. c=300,000,000\, m/s (approximately, let’s not split hairs). The speed at which data is sent depends on the refractive index, which is a ratio of how fast light travels in a medium compared to a vacuum. In glass, this value is about n=1.5 for visible light, meaning that a signal in optical glass fibres may travel at:

v=\frac{c}{n} = \frac{300,000,000}{1.5} = 200,000,000\,m/s\tag{16}This means that it takes the network about 1/200,000,000=5\,ns (nanoseconds) to send data for 1 metre through the network. Our CPU, in the meantime, is able to perform calculations according to its clock cycle, which is about 2-3 GHz on HPC clusters. This means it takes the CPU about 1/3,000,000,000=0.3\,ns to perform one operation. If two nodes are separated now by one metre, the CPU can perform 5/0.3\approx 16 operations while data is being sent over the network.

This does not include the time it takes to read data from RAM and put it onto the network, and write it back into RAM at its destination. What this calculation shows is that as our compute nodes are getting separated physically in space, the time it takes to send data becomes a bottleneck. Who would have thought that the speed of light is not fast enough for CFD applications!

Returning to our weak scaling problem, as we increase the number of cores, we don’t just increase the number of communications that need to happen, similar to strong scaling, but we also test how the additional distance in space affects the communication speed.

In general, when we try to benchmark our CFD applications, we perform a strong scaling analysis, and usually, we are happy with that. Weak scaling is not often done. You only really need weak scaling if you are targeting really large simulations (1000 cores or more, let’s say), but most of the time, this analysis will not give you any actionable insights to improve your parallel efficiency.

Weak scaling is usually much more important for those who maintain the HPC facilities and try to identify bottlenecks, or just to benchmark their system. If we performed two separate weak scaling tests on two different systems, we likely would get different results. In a sense, the weak scaling results are mostly influenced by the HPC system itself rather than our code.

Thus, if we wanted to improve our code, especially our parallel efficiency, we would perform a strong scaling analysis and try to improve our communications here. Any improvements made in strong scaling would also show in weak scaling, though the bottleneck in weak scaling would still be the system that we use.

Let’s look at another example, say we have to look at a simulation where we have kept the problem size the same. For the sake of argument, imagine we run a problem where the meh size is exactly 1 million cells per core, and we measure the computational time it takes as we add more and more cores, keeping the number of cells per core the same. Example measurements can be found in the table below:

| Number of cores (required nodes) | Measured time (in seconds) |

|---|---|

| 1 (1 node) | 0.58 |

| 2 (1 node) | 0.63 |

| 4 (1 node) | 0.72 |

| 8 (1 node) | 0.79 |

| 16 (1 node) | 0.89 |

| 32 (1 node) | 0.97 |

| 64 (2 nodes) | 1.03 |

| 128 (4 nodes) | 1.26 |

| 256 (8 nodes) | 2.41 |

| 512 (16 nodes) | 4.59 |

| 1024 (32 nodes) | 10.69 |

| 2048 (64 nodes) | 22.01 |

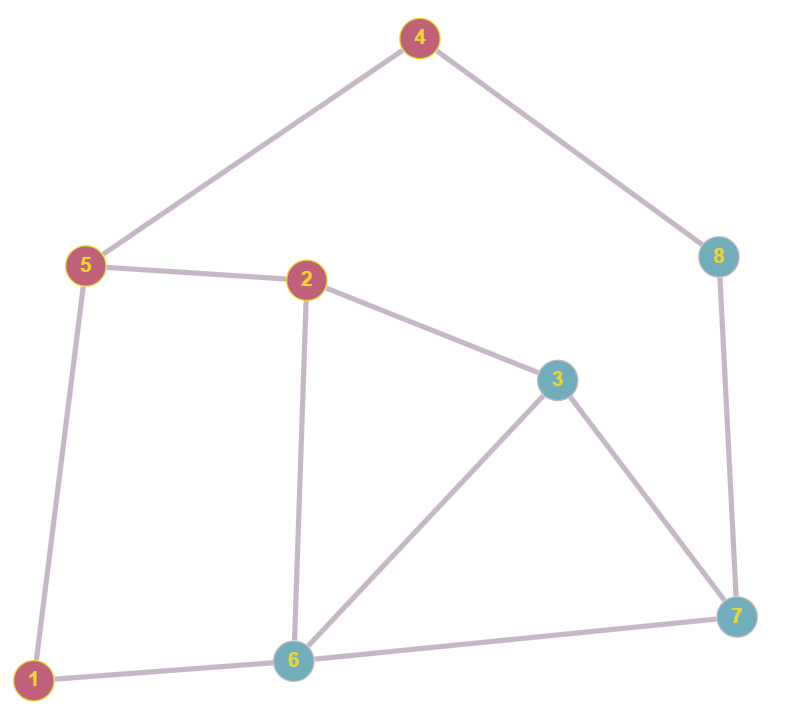

We can now compute the efficiency again, this time expressed as:

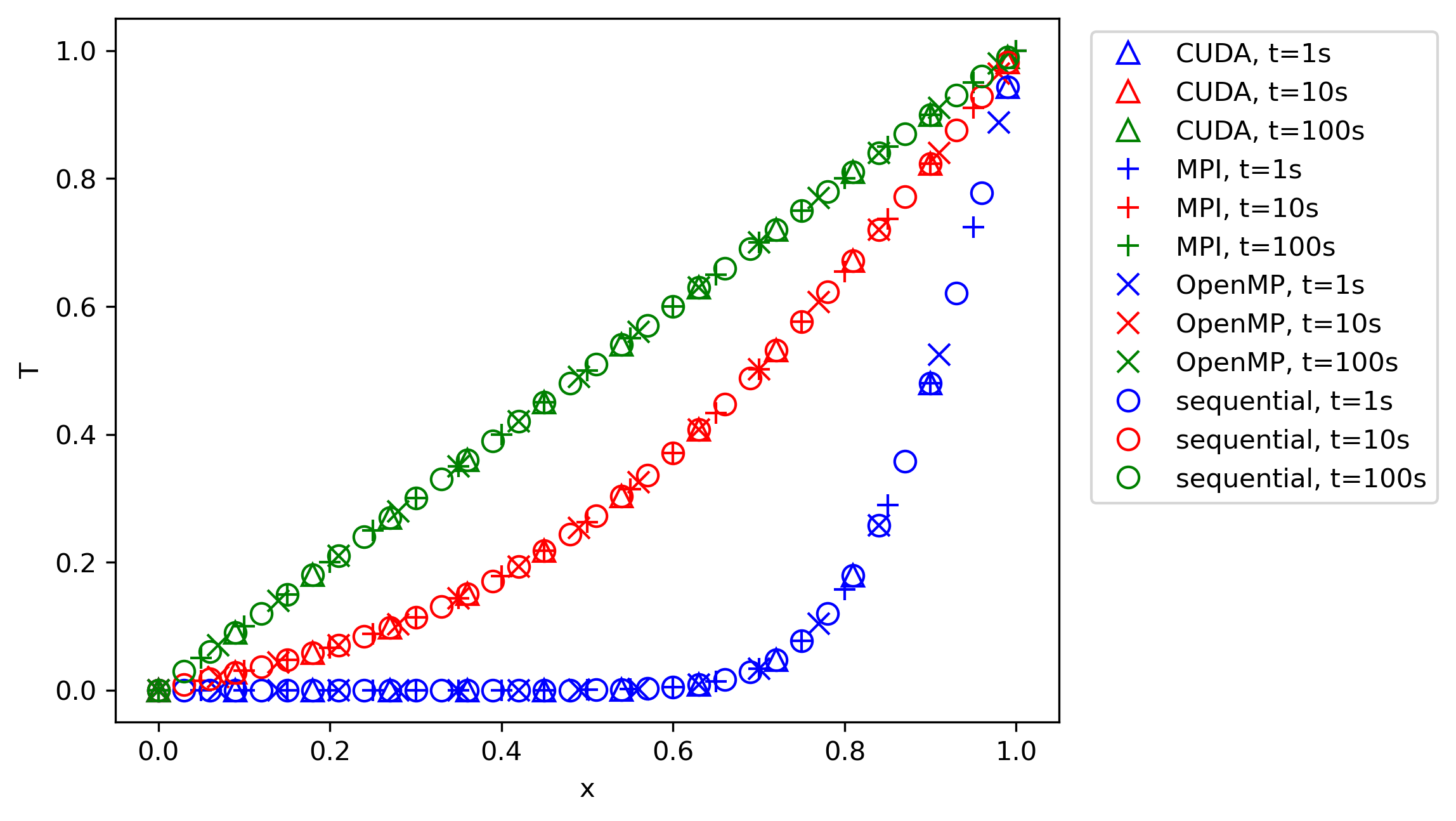

E(p, N)=\frac{T(1,N)}{T(p,N)}\tag{17}Thus, we take the time it took to run this simulation on one core (i.e. 0.58s) and compare that to subsequent simulations. In an ideal world, as the number of cores increases and the problem size per core remains the same, we would expect the computational time to be the same. While the computations don’t change, the time we have to wait for data will increase, and so we will see a departure from a 100% efficiency. This is shown in the following figure:

This is all there is to weak scaling, really. But one question is still open. After we have done our strong and weak scaling, how can we determine the number of cores to use that is optimal for our simulation? This is the question we seek an answer to in the next section.

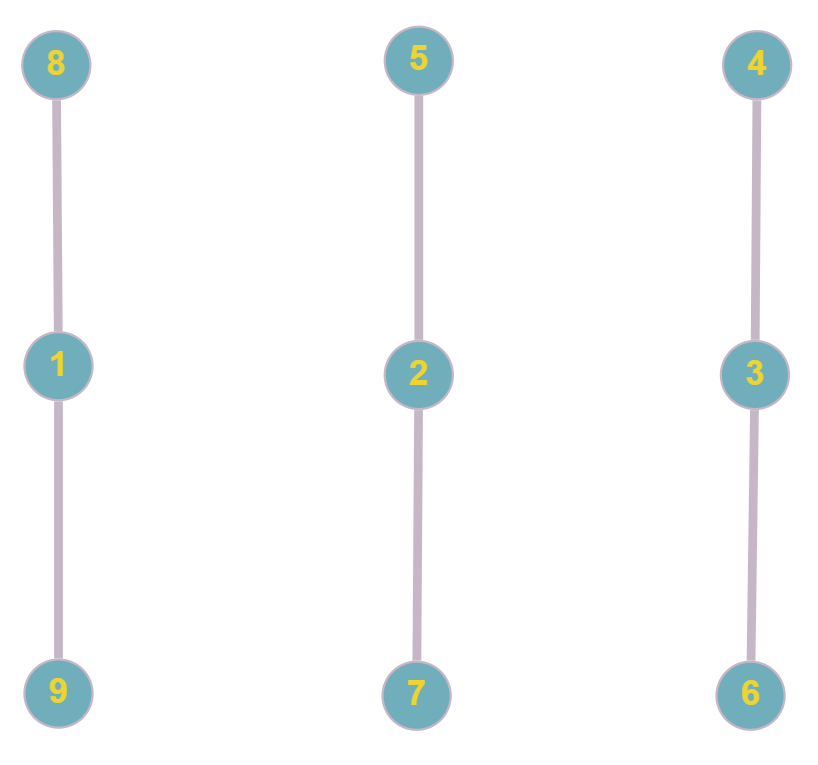

The optimal number of cores for your simulation

Indeed, if we just did the strong and weak scaling to plot some fancy plots, we would have wasted quite a lot of computational resources for one figure. If this figure then never gets used, for example, in a publication, then what was the point of this exercise? Typically, we want to perform the strong scaling so we can compute an optimal problem size per core, that is, for how many cells per core do I still get a good speed up with a good parallel efficiency.

As we have seen both in the strong and weak scaling sections, it is impossible to get something with a parallel efficiency of 100%, unless we use a single core (at which point, we don’t have parallelism, so this is a pointless answer). So, first we have to settle on a level of parallel efficiency we are happy with, and then we can try to identify a suitable problem size per core.

A good rule of thumb is that 75% – 80% is an acceptable parallel efficiency, so when you perform your strong scaling, you look at which point you reach a value of 0.75 \ge E(p, N) \ge 0.8 and then find the number of cores and the problem size. Say you achieved this value with 8 cores and your problem size was 1 million cells. Then, you can compute the optimal problem size as:

N_{opt} = \frac{N}{p|_{0.75 \ge E(p,N) \ge 0.8}} = \frac{1,000,000\,cells}{8\,cores} = 125,000\frac{cells}{cores}

\tag{18}

Once you have performed this analysis, you have generalised your strong scaling results and extracted some actionable insights. If I come along and I want to use your code, and my simulation uses 15 million cells, then you can tell me that the optimal number of cores is 15,000,000/125,000=120. Except, it isn’t! The correct answer is either 64 or 128.

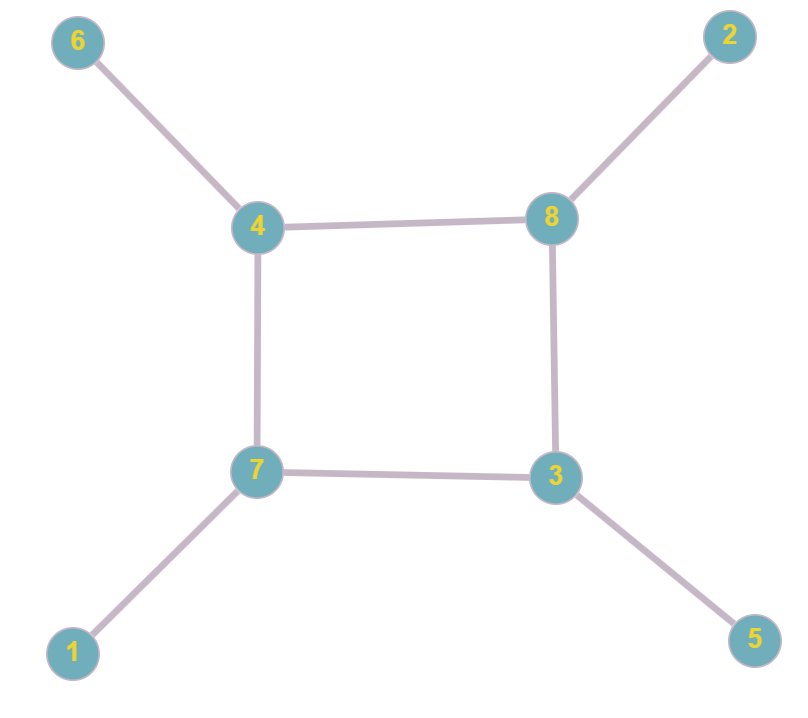

To understand that, let’s consider the HPC hardware. We have our different cabinets and compute nodes, and we need to connect them all together. What is the optimum way to connect them? Well, HPC interconnection is a topic in itself, but let’s just say that all of the common topologies we use, like the hypercube or Torus, require 2^m connections (where m is an integer). For example, if you follow the link to the hypercube, it will say:

“Hypercube interconnection network is formed by connecting N nodes that can be expressed as a power of 2. This means if the network has N nodes it can be expressed as:”

N=2^m\tag{19}Similar observations can be made for the Torus interconnect. Thus, if we have 2^m network links connecting different compute nodes together, then it would make sense to have 2^n cores to efficiently use this network (where n is an integer). If we use a number of cores that can not be expressed as 2^n, then we don’t utilise the network efficiently.

On the parallelisation side of things, there will be algorithms that expect us as well to use 2^n cores. Some algorithms are implemented in a way that expects either 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, … cores, so that it can always divide a problem into 2 and then distribute that amongst cores. If I have one computation and want to split it into 2, I get 2 sub-problems to solve. If I divide this again by 2, I get 4 sub-problems. Divide that again by 2, I get 8, and so on.

If I come now with 12 cores, then I cannot efficiently distribute that problem. Our parallelisation framework will be able to handle 12 cores, but it has to do some additional work, which slows us down. If we just come with 16 cores instead, we can nicely subdivide our problem into 16 sub-problems, which allows for fast execution.

Coming back to our example of me wanting to use your code with 15 million cells, the answer is not 120 cores, but rather 64 or 128, both of which can be computed with 2^n. In this case, I would probably select 128, as this is really close to 120 and 15,000,000/128\approx 117,000, so it is not miles away from the theoretical optimum (which will likely also contain some variance).

Thus, when we want to determine the optimal number of processors, this is the generalised approach:

- Perform strong scaling analysis of a problem size that is sufficiently large.

- Compute the parallel efficiency and identify the number of cores required to retain a 75% – 80% efficiency.

- Compute the optimal number of cores as we have done in Eq.(18). This will be your lower bound C_{lower}.

- Multiply the optimal number of cores by 2. This will be your upper bound C_{upper}

- Determine the value of n for which the following inequality is satisfied: C_{lower} \le C_{given} / 2^n \le C_{upper}. Here, C_{given} is the number of cells of the problem we are trying to solve.

- Calculate the number of cores as N_{cores} = 2^n.

You can do that, write your own calculator for that, or, shameless plug, use my browser extension, which has a parallel computation calculator that will do all of that for you. If you don’t want to use the calculator, or even write your own, here are some good default values:

- Assume that commercial CFD solvers will retain a parallel efficiency of about 75% – 80% for 50,000 – 100,000 cells per core.

- Assume that in-house (academic) codes or open-source CFD solvers, unless touched and optimised by some HPC wizard, retain a parallel efficiency of 75% – 80% for 100,000 – 200,000 cells per core.

If I leave this discussion here, someone will inevitably point out a flaw that I have used throughout my discussion up to this point. I have always been referring to our problem size as the number of cells in our simulation. However, the number of cells is not necessarily a good indicator of the amount of work we do. For example, the work done on a 4-million tetrahedral-dominant mesh and a 1-million polyhedral-dominant mesh may be the same.

In reality, the number of faces, not the number of cells, determines our computational cost (assuming we are using a finite volume method). So, if you just want to be that extra bit pedantic, or you are German, then use the number of faces, not the number of cells. I was thinking how I could show you why Germans are the way they are, I don’t think I can, but here is a good summary of German values …

The music is meh, but the lyrics are, well, I shall not spoil them. If you are interested, here is a somewhat decent translation. It really brings out that German arrogance that people in the world have come to love about us (I think …).

The reason we use the number of cells to determine the computational cost is due to historical reasons. When we started to do CFD in earnest around the 1950s, with pioneering work of Lax, Friedrichs, Harlow, Welch, all was done in 1D and 2D on structured grids. Since structured grids only allow for a single cell type, it doesn’t matter if we take the number of cells or the number of faces. The work will scale well with either metric.

Only once the finite volume method was introduced in 1971 by McDonald and, independently, in 1972 by MacCormack and Paullay, did we start to adopt new elements that could be treated by the finite volume method, including polygons (2D) and polyhedra (3D). Since polygons and polyhedra elements can have an arbitrary number of faces, using the number of cells is no longer a good indication for the computational work, as the finite volume method is face-based, that is, integrals/fluxes are evaluated at the faces.

Therefore, we ought to use the number of faces, and not the number of cells, when we talk about computational cost, but I suppose this is yet one more example of how CFD is full of wonderful inconsistencies.

People in the finite element community, however, have realised that the logic we are using is flawed, and so when they talk about problem sizes, they use the term degrees of freedom, which also accounts for the fact that you may have a different number of integration points per cell.

In any case, I have admitted the logical inconsistency, so you don’t have to tell me that I am wrong.

The roofline memory model

When we did our strong scaling analysis, we wanted to identify when our performance is dropping. We used the efficiency to guide us in this case, and we ended up with the smallest problem size per core that still gives us an acceptable parallel efficiency.

Let’s say after we have obtained this number, we realise that our code is just very slow, but we don’t know where this is coming from. So, we want to benchmark our code to identify the bottleneck, so that we know which part of the code we have to improve. This is where the roofline model comes in. Arguably, it is a simple model, and much more sophisticated models are available, but it helps us to identify which bottleneck we have, and we have two possible solutions. Either we are:

- Memory-bound

- Compute-bound

If we are compute-bound, it means that we are already utilising our CPU to its maximum capacity. We cannot squeeze more out of our CPU by giving it more work to do; if we wanted to get more performance, we would need to get a CPU with a faster clock cycle (i.e. get a CPU with more GHz).

If we are memory-bound, however, then our CPU is not getting enough data to operate on. Either the CPU is not doing enough with that data before it requests new data, or our memory supply is not optimised. Typically, we have enough data for the CPU to work on, so if we are memory-bound, it usually indicates that we are very inefficient with our memory access.

Let’s create an example to understand how memory access can cause a bottleneck and result in our application being memory-bound. Let’s say we want to perform a simple vector matrix multiplication. This is something we routinely do in our applications, and so you may have a few of these in your code as well. Let’s look at a very simple example:

#include <vector>

using MatrixType = std::vector<std::vector<double>>;

using VectorType = std::vector<double>;

int main() {

int N = 1024;

MatrixType A(N, std::vector<double>(N));

VectorType x(N);

VectorType b(N);

// fill data for A, x, b. Not done here, a real application would do that.

// ...

// b = A * x

for (int j = 0; j < N; ++j) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

b[i] += A[i][j] * x[j];

}

}

return 0;

}I have defined two types on lines 3-4 to allow me to create a matrix (consisting of two std::vectors arranged as a 2D matrix) and a vector (consisting of a single std::vector). I use these types to create the matrix A and the two vectors x and b on lines 9-11, using the number of elements per row/column as defined by N (which would be, for example, the number of cells in our mesh).

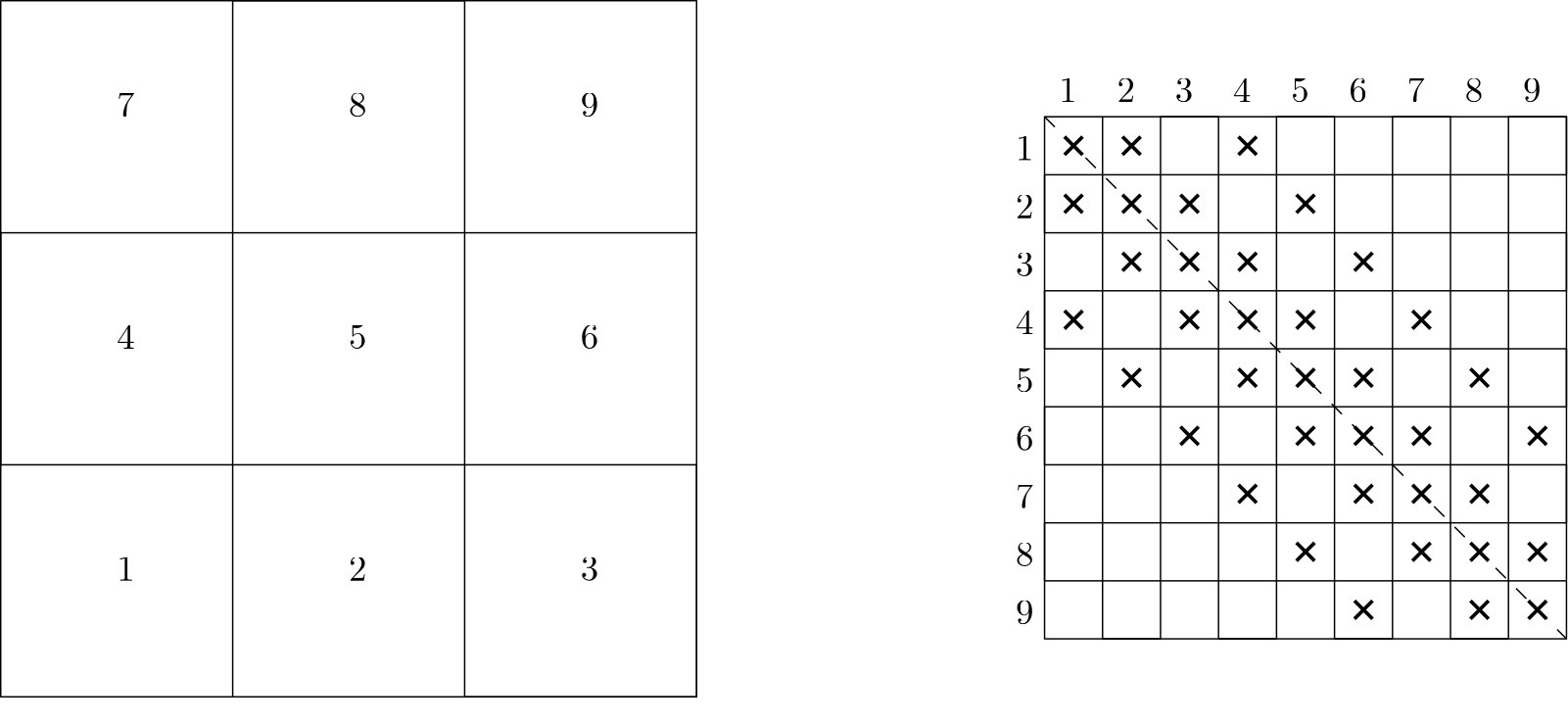

On lines 17-21, I perform the vector matrix product, i.e. b = Ax. If your programming background is from Fortran, then this will look familiar to you. We have two loops, and we first loop over j (columns), and then over i (rows). The order in which we would access our matrix is shown in the following:

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 4 & 7 \\[1em]

2 & 5 & 8 \\[1em]

3 & 6 & 9

\end{bmatrix}\tag{20}Because we are accessing each column one after the other, we call this the column major ordering. But, we could have also reversed the loops and have:

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; ++j) {

b[i] += A[i][j] * x[j];

}

}In this case, the matrix would be accessed in the following order:

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 2 & 3 \\[1em]

4 & 5 & 6 \\[1em]

7 & 8 & 9

\end{bmatrix}\tag{21}Because we are going through the matrix row by row, we call this the row-major ordering. The question is, which of these is better suited to compute the vector matrix product? It all depends on how C++ stores variables, and it does that in row-major order. To confirm this, we could benchmark both vector matrix multiplications and see which is faster. I have done just that and used Google Benchmark to time both versions. There is a handy website that helps us do that called QuickBench, which I have used.

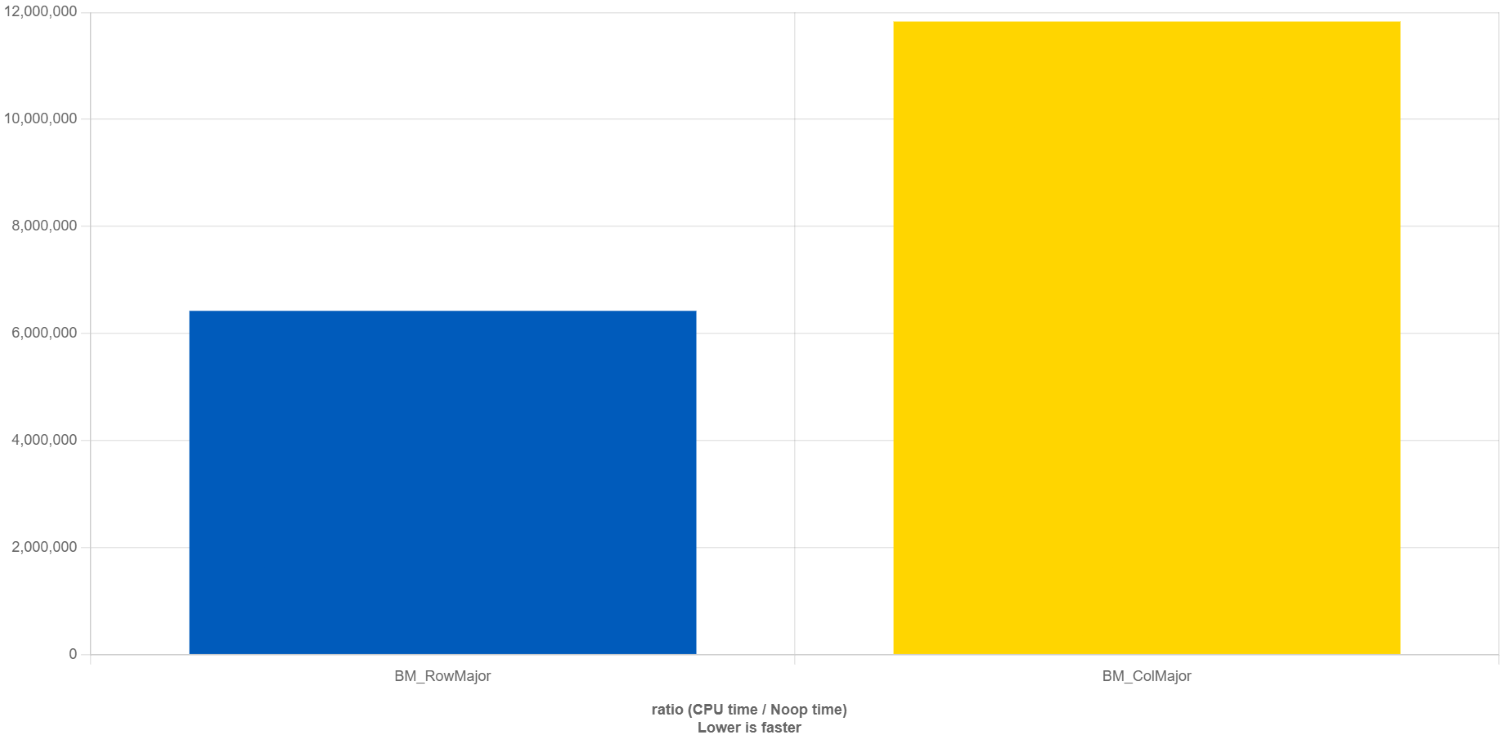

The result from this comparison is shown below:

What QuickBench is doing is to compute the time it takes to perform a no-operation (noop, great name!) function call (i.e. calling a function that doesn’t do anything), and then comparing that time against the time it takes to compute our row major and column major matrix vector multiplication, so the y-axis is a non-dimensional unit of time.

Thus, the smaller the bar, the shorter the execution time. We can see that the row-major matrix vector multiplication on the left (blue bar) takes about 1.8 times less time to compute than the column-major matrix vector multiplication. What we learn from this is that we should always use i,j,k loop variables, not k,j,i when looping over multidimensional arrays. But why?

Remember when we talked about the memory hierarchy, I said that whenever the CPU needs new data in its registers to perform a computation, it will request that data from the L1 cache. If it is available, then it can load that data quickly and continue its computations; otherwise, it will have to wait for the L1 cache to request the data from the L2 cache. If it is there, the L1 cache will get this data quickly; if it is not, the L2 cache needs to request it from the L3 cache, and the L3 cache may have to go to RAM to get the data.

Whenever the CPU request the next element in an array (be it a 1D vector or a multidimensional array), we don’t just load a single element into our caches, but rather, we fill our caches with as much memory as possible so that when we request the next element, it will already be available. Whenever we request data, and it is already available in our cache, then we have a cache hit. If it is not available, we have a cache miss. Whenever we have a cache miss, we need to go back to the next cache or RAM to get additional data.

Getting the data will take time, and so we want to minimise cache misses as much as possible. The way to do that is to align our memory access with the way C++ stores its data. Let’s take a simple example and say that we have the following matrix:

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & -1 & 2 \\[1em]

7 & 4 & -4 \\[1em]

5 & -3 & -2

\end{bmatrix}\tag{22}Let’s say that our CPU can hold 3 doubles in their register. With a row major memory access, we would first load 1,\, -1,\, 2 into our register. If we now also had the vector x loaded into another register, then we could compute the first entry into our b vector as 1x_0 -1x_1 + 2x_2. Since both the first row of our matrix and the vector x are in our registers, we were able to perform this operation without going back to our caches to request additional data.

To complete the first row in our vector matrix multiplication, we have to, yet again, request a new line column from our matrix, now 2,\, -4,\, -2, and we can calculate 2x_2. We can add that to the previous accumulated sum. Thus, to compute the first row, we had 3 memory loading instructions for our matrix using column-major memory access compared to 1 memory loading instruction for our row-major memory access.

If you continue this for the second and third row, you will end up with 3 memory load instructions for row-major memory access and 9 memory load instructions for column-major memory access. Memory is expensive, even with a clever cache hierarchy, and for that reason, we see that column-major memory access is 1.8 times slower than row-major memory access in our benchmark performed above.

So, the question then is, how do we know if our application is already saturated and using all the available power from our CPU (i.e. we have a compute-bound problem), or if we are having bad memory access and need to think about how to optimise this? This is where the roofline model comes in.

The roofline model defines two properties: the theoretical max performance of our CPU, measured in GFLOPs (giga floating point operations per second), that is, how many billion arithmetic operations can be performed on floating point numbers per second, and the operational intensity, measured in FLOPs/byte.

We need to define two units here. First, we have to consider the work performed. This is given the letter W, and this would be related to the work the CPU is doing, typically, how many floating point numbers it can work on per second. For this reason, we typically use GFLOPs when plotting the roofline model.

The second unit we need to look at is the memory traffic Q, and it measures how much data was requested by the CPU to perform its work W. With both of these numbers defined, we can compute the arithmetic intensity I as:

I=\frac{W}{Q}\tag{23}

This gives us a ratio, which essentially tells us how much data we need to perform a given number of operations. For example, let’s look at the following two operations:

a = a^2 + a \\[1em]

b = c * d\tag{24}

In the first example, we need to load 1 floating point value $a$ to perform two floating point operations, and then we need to store one floating point number. Let’s say that $a$ is a “`float“`, which typically takes 4 bytes of storage. Then, we can say that we have 1 load and 1 store operation, which takes 8 bytes in total. We have 2 floating point operations, i.e. $a^2$ and then the addition of $a$ with that result. Then, our arithmetic intensity would be:

I=\frac{W}{Q}=\frac{2}{8} = 0.25\,\, FLOPS/Byte \tag{25}

Let’s look at the second example. We have two load instructions of $c$ and $d$, and one store instruction for $b$. We have one floating point operation, i.e. $c \cdot d$, so we have an arithmetic intensity of:

I=\frac{W}{Q}=\frac{1}{12} = 0.08\dot{3}\,\, FLOPS/Byte \tag{26}

Now we need to look at the peak bandwidth of our system. The peak bandwidth is the maximum memory transfer rate between the CPU and memory. It is usually measured in GB/s. The easiest way to figure that out is to use a benchmark tool that will run some calculations, where the amount of memory to be transferred is known, so measuring the time it takes to transfer that data can be used to compute the bandwidth. A common benchmark is the [STREAM benchmark](https://github.com/jeffhammond/STREAM), and on my PC, I am getting values between 35 – 50 GB/s, depending on the operation.

Knowing this value, we can now compute the performance as the product of the peak bandwidth, let’s call that $\beta$, and the arithmetic intensity $I$. In our examples above, we would get the following performance:

P = \beta\cdot I = 50\frac{GB}{s}\cdot 0.25\frac{FLOPS}{Byte} = 12.5\frac{GFLOPS}{s}\\[1em]

P = \beta\cdot I = 50\frac{GB}{s}\cdot 0.08\dot{3}\frac{FLOPS}{Byte} = 4.1\dot{6}\frac{GFLOPS}{s}\tag{27}